‘I pretended to be somebody I wanted to be until, finally, I became that person, or he became me’. (Cary Grant)

Introduction

Cary Grant, born as Archibald Leach in a working-class area of Bristol in the South West of England, UK in 1904, became one of Hollywood’s most celebrated stars, hailed as the ‘best and most important actor in the history of cinema’ by David Thomson (1975). Although numerous commentators have recognised the significance of Grant’s national identity – his Britishness – to his star persona, this article seeks to rethink his identity as specifically Bristolian, exploring the ways in which that regional identity complicates the meaning and significance of his star persona. It does so through an extended case study of the biennial Cary Comes Home Festival in his hometown Bristol, exploring the ways in which the festival has encouraged a re-evaluation of Grant’s star identity, the depth and range of his connections with the city and his posthumous role as a cultural ambassador. The article will argue that the festival has helped to increase understanding of Bristol’s screen heritage (and sense of itself as a city of culture) that included the city’s recognition as a UNESCO City of Film in 2017, as well as having an economic function in promoting film tourism to the city.

The article discusses the aims and objectives of the festival, outlines its development and critically reflects on curatorial practice. It locates the festival within screen tourism including fan practices of ‘pilgrimage’ to sites that have a particular, quasi-sacred significance, and analyses how the material landscape of Bristol informs visitors’ understanding of Grant’s identity. This discussion relates these areas of screen tourism to the emerging literature on festival studies, focusing on the role of curatorial practices and the various ways in which they try to manage the tension between a cultural and educative function, and an economic role in creating a ‘brand’ that might draw tourists to the city.

You Can’t Take Bristol Out of the Boy: Grant’s Complex Star Persona

Even though he spent his entire film career working in Hollywood, various commentators have recognised that part of Grant’s complex identity was his Britishness. In a famous essay, ‘The Man from Dream City’, Pauline Kael argued: ‘Grant was English, so Hollywood thought he sounded educated and was just right for rich playboys, but he didn’t speak in the gentlemanly tones that American moviegoers think of as British’ (1975: para 11). As Kael points out, Grant’s projection of Englishness was distinctively different from the conventional gentlemanliness of Ronald Colman and other contemporaneous British actors which, she recognises, was partly a product of Grant’s working-class upbringing:

Grant’s romantic elegance is wrapped around the resilient, tough core of a mutt, and Americans dream of thoroughbreds while identifying with mutts. So do moviegoers the world over. The greatest movie stars have not been highborn; they have been strong-willed (often deprived) kids who came to embody their own dreams, and the public’s. (1975: para 9)

Unsurprisingly, Kael does not appreciate how this working-classness, and indeed Grant’s whole persona, is imbued with his Bristolian identity. It is there in his famous and much imitated accent, which contains a remnant of the distinctive West Country burr (which Kael miscasts as Cockney), a trace that suggests Grant never quite left the city of his birth. It was an enduring relationship: Grant returned once or twice a year to see his mother and even after she died: ‘I still go there often because Bristol is a beautiful city with no pollution, a charming place. It’s one of my favorite places in the world. I also have cousins there’ (quoted in Cohn 1976: 29). However, Bristol’s importance was not limited to sentimental ties, it was bound up with his whole identity in a dialogic relationship between Archie Leach and Cary Grant.1 Grant himself recognised that this was an ongoing, emotionally taxing and difficult process:

I have spent the greater part of my life fluctuating between Archie Leach and Cary Grant; unsure of either, suspecting each. Only recently have I begun to unify them into one person: the man and boy in me, the hate and the love and all the degrees of each in me, and the power of God in me. (Grant 1963)

This tension between Archie Leach and Cary Grant became a key part of his star image, an identity that crystallised the yearning of a working-class Bristol boy, born in a port on the west coast of England which looked to America as the country in which the glamour and dreams that could not be fulfilled in Britain, where the class system was much more restrictive and opportunities for success and upward mobility far more limited, could be achieved. As Xan Brooks suggests, Grant’s ‘Bristol connection … was the making of him…. Rather than a disowning of Archie Leach, Grant was just Leach’s immaculate conception of himself’ (2001: para 22).

Although rags to riches stories were common in Hollywood, Grant’s was unusual in that he chose not to hide it (Glancy 2020: 76–77). Unlike some stars such as John Wayne who bury their originating identity, Steven Cohan (1997) argues that part of the fascination of his onscreen persona, particularly in films of the 1950s, comes from the ways in which he draws attention to the masquerade of masculinity. Grant’s ongoing appeal is that he lets us in on that masquerade. Audiences are invited to understand that Grant’s persona – like all star images – is a fantasised construction: ‘Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant’ (quoted in McCann 1996 and Eliot 2005). Thus, in many ways understanding the significance of Bristol to Grant is an important element in understanding the nature of his star persona. The remainder of the article explores the ways in which this understanding can be conducted through the ongoing, practice-based curatorial activities embodied in the Cary Comes Home Festival. I want first to examine the impetus for setting up the festival: my own awakening, as a Bristolian, to his profound connection to the city.

The Origins of the Cary Comes Home Festival

The Cary Comes Home for the Weekend Festival – to give its full title – is a biennial festival dedicated to celebrating ‘Cary Grant’s Bristol roots, developing new audiences for his work and recreating the golden age of cinema-going’ (Cary Comes Home Website). It was established in 2014 by the author and Anna Farthing and has so far had four iterations (2014, 2016, 2018, 2020), plus events in the intervening years, including celebrations of his birthday (18 January), Valentine’s Day, Halloween and Christmas screenings. The festival’s central ambition is to increase an understanding of Grant’s ongoing relationship with the city after he became famous and reflect on how his association with Bristol feeds into a wider understanding of the city’s screen heritage. A further aim is to trace the material specificities of that association, as well as their context within a socio-cultural history of the city and the impact that this had on the development of Grant’s star identity.2

Indeed, the festival was inspired by the actual places that he knew intimately, including the now demolished cinemas he frequented as a child and the Bristol Hippodrome theatre (still standing) where his dreams of performing were first hatched. Whilst researching Bristol’s screen heritage for the Lost Cinemas of Castle Park app (Crofts 2013b), I identified several Bristol city centre sites Grant mentions in his autobiography (Grant 1963), including two very different cinemas he used to frequent with each of his parents separately. Archie’s aspirational mother took him to Clare Street cinema ‘the town’s most elite … where one could take tea while watching the films, and where I was first introduced to a pastry fork’, whereas his father took him to The Metropole in St Pauls, a fleapit that ‘smelled of raincoats and galoshes, and no tea or pastry forks. Yet it was, of the two, my favorite place’ (Grant 1963). At a third cinema, the Scala Cinema on Zetland Road (Glancy 2020: 19),3 Grant recalls attending the Saturday matinees ‘free from parental supervision’ where ‘Charles Chaplin, Ford Sterling, Roscoe Arbuckle, Mack Swain and John Bunny with Flora Finch, together with Bronco Billy Anderson, the cowboy star, were our greatest favorites’ (Grant 1963). Thus, cinema-going and the specific buildings that he went to as well as the films and stars that he watched, form part of Grant’s key memories of Bristol, his embrace of popular pleasures and the power of entertainment that informed his whole persona.

Grant also worked at two Bristol theatres, the Bristol Hippodrome and the Empire Theatre – both of which briefly operated as cinemas at the height of Bristol’s cinema-going in the 1930s – that helped form his fascination for performing that shaped his whole career. He was originally introduced to the Hippodrome on a school visit with the chemistry assistant at Fairfield Grammar, who had recently installed the switchboard and new electric lighting system:

The Saturday matinee was in full swing when I arrived backstage; and there I suddenly found my inarticulate self in a dazzling land of smiling, jostling people wearing and not wearing all sorts of costumes and doing all sorts of clever things. And that’s when I knew! What other life could there be but that of an actor? They happily traveled and toured. They were classless, cheerful and carefree. They gaily laughed, lived and loved. Yet? H’m. Little did I know. But an actor’s life for me. And how was I, still only thirteen years old, to join them? (Grant 1963)

Grant became ‘obsessed’ with the Hippodrome (Glancy 2020: 19) and eventually secured a job there as a call-boy; he also worked for a short time at the Empire Theatre as a lighting assistant but was fired for revealing the mechanism of a magic trick. He returned to work at the Hippodrome where he met the Pender Troupe of Knockabout Boys, with which he toured the UK and emigrated to America in 1920. Archie stayed on in America when the Penders returned to London, spending over a decade in New York, before making his way out to Hollywood. Little did young Archie know when he first visited Hippodrome and yearned for the life of an actor, that his image would later beam down from the silver screen when it temporarily converted to a cinema between 1932–39.4 It was this interconnectedness between Grant’s Bristol past, his future stardom, and the present existence of the theatre as it is today, that excited me about the idea of showing his films there once again and Cary Comes Home was born. I felt instinctively that bringing Grant’s films back to the theatre where he began would create a unique and compelling experience for Grant fans, building on knowledge gained through user-testing my locative-media heritage apps, the Curzon Memories App (Crofts 2011, 2012a, 2012b) and The Lost Cinemas of Castle Park (Crofts 2013b). Both apps were designed to be experienced ‘on location’, triggering context-sensitive content aimed to bring cinema history to life in the places where it actually happened. Thus, the user experience aimed to ‘harness that serendipitous frisson between user interface, media content and the location itself’ (Crofts 2013a). Right from the start, then, the guiding aim of the festival was to programme immersive cinematic experiences in dispersed locations that were significant to Grant’s life, including the places where Grant was photographed by Bristol Evening Post on his many visits home (see Figures 1 and 7).5

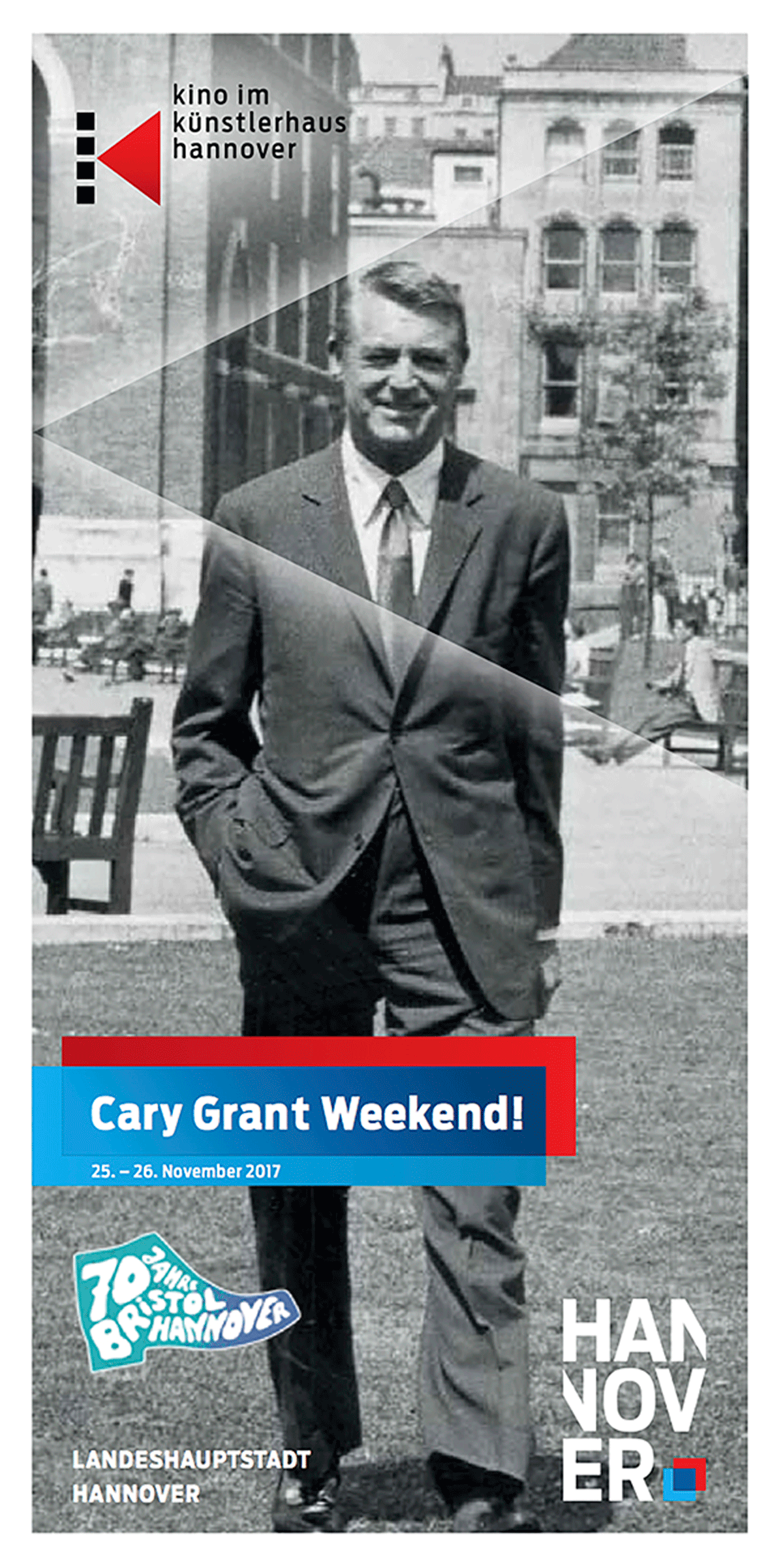

Cary Grant on College Green in the 1957, Bristol © Bristol Post.6

Film Tourism and the Role of Film Festivals

Although our primary motivation is, in a sense, to give Grant back to Bristol and Bristolians, the festival also seeks to encourage a wider participation, attracting national and international film tourists. Sue Beeton argues that film tourists’ motivations are complex: ‘visitors were coming to film sites to re-live an experience (or even emotion) encountered in the film, reinforce myth, storytelling or fantasies, or for reasons of status (or celebrity)’ (2010: 2, my emphasis). Macionis (2004) differentiates between film tourists whose primary motivation is intersocial and motivated the desire for novelty, rather than specifically cinematic and those who are motivated by locations they have seen in films, which she suggests is related to the idea of pilgrimage (see also Tzanelli 2004, 2010). Urry and Larsen see the tourist as ‘a kind of contemporary pilgrim, seeking authenticity in other “times” and other “places” away from that person’s everyday life. Particular fascination is shown by tourists in the “real lives” of others which somehow possess a reality which is hard to discover in people’s own experiences’ (2011: 8). Thus, cinematic tourism extends not only to paying homage to film locations (‘set-jetting’), but also to the places that have a physical connection to actors and celebrities, including their place of birth: ‘it seems that to physically be in the place … is a strong motivation for the film-induced tourist’ (Macionis and Sparks, 2009: 100, original emphasis).

Although the festival attempts to cater for the varied motivations of film tourists, our curatorial practices are primarily informed by and contribute to the emerging discipline of Film Festival Studies (Film Festival Research Network 2019), which has become increasingly concerned with the experiential aspects of film festivals rather than a narrow focus on their economic impact, acknowledging the need for more qualitative research in this area (Flores Ruiz et al 2017). Jansa argues that:

festivals are rather the site where cultural and power conflict can occur and where cultural negotiations take place. Festivals construe a space for the generation of narrative, experience and memory. As such, they are a public sphere in which all involved actors actively participate and are simultaneously influenced by this sphere as well as shaping it. (2017: 205)

Similarly, de Valck applies Victor Turner’s idea of ‘communitas’ to film festivals, arguing that they ‘are indispensable in the creation of symbolic value’ forming ‘a zone, a liminal state, where the cinematic products can bask in the attention they receive for their aesthetic achievements, cultural specificity, or social relevance’ (2007: 37; see also Flores Ruiz 2015; Flores Ruiz et al 2017). Drawing on Bourdieu’s concept of ‘symbolic capital’, de Valck identifies the role of festivals as ‘taste-makers’, not only providing ‘cultural consecration’ but also ‘cultivating audiences’ and sustaining ‘a system of cultural legitimization’ (2007: 37). Rastegar also argues that through curating films, festivals ‘create and expand taste’ (2016: 192).7

Although de Valck and Rastegar focus on contemporary industry-based film festivals such as Cannes at which new films are screened, their insights can equally be applied to revival festivals, such as Cary Comes Home. As Julian Stringer points out, ‘many festivals also embody a backward-looking sensibility’ in which ‘“old” or “classic” movies’ are merely recirculated (2003: 82). However, Stringer argues such events have the potential for ‘different kinds of historical agendas’, ones that open up spaces ‘for a more decentred and de-territorialised view of Hollywood’s reception history’ (Stringer 2003: 95). Thus, the planning of Cary Comes Home, rooted in a determination to reanimate sites that were significant in Grant’s life, sought to promote the experiential dimensions of cinema-going, to trigger memories through encouraging active participation, to pay careful attention to the film aesthetics and so inform and expand horizons of taste and to resituate classic texts in ways that might encourage their re-evaluation. Before moving on to evaluating the overall impact of Cary Comes Home, I will discuss its curatorial strategies.

2014 Festival

The first Cary Comes Home Festival, which took place over the weekend of 11–12 October 2014, adopted a ‘dispersed’ approach encouraging participants to directly experience and engage with a variety of locations that had different significances for Grant, some of which would satisfy the fan pilgrim’s desire to visit the special or ‘sacred’ place.8 The main locus for this was, naturally, the Bristol Hippodrome, the venue whose close associations to Grant had inspired the festival, culminating in a red-carpet gala double bill of Arsenic and Old Lace (dir. Frank Capra, 1962) and North by Northwest (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1959), two contrasting films that display different aspects of Grant’s performance style. The choice of films may have been conservative, mainly because of the imperative to cover costs and attract an audience, but the festival’s determination to relocate Cary Grant as a Bristolian was embodied in several ways, foregrounding the dialogic relationship between the actor Cary Grant and his younger self and attempting to open up Stringer’s ‘different kinds of historical agendas’. This was encapsulated in a live performance by local youth drama school The Big Act, re-enacting the life of Archie Leach on the Hippodrome stage before the first screening (see Video 1).9

Cary Grant Comes Home For The Weekend red carpet gala screenings.

The programme included other ‘wrap-around’ content to enhance and extend the cinematic experience, including a live pianist in the piano bar, its front of house staff sporting vintage cinema usher costumes and the Hippodrome choir singing swing classics as part of Bristol Festival of Song, all designed to recreate something of the lost atmosphere of the golden age of cinema-going that Grant embodies. The festival also encouraged audience participation with a best-dressed competition, inviting participants to don vintage Hollywood attire and be snapped on the red carpet by UWE Filmmaking and Journalism students pretending to be paparazzi whilst also documenting the event (see Videos 1 & 2 and Cary Comes Home Website (2020) and Cary Comes Home Facebook (2020) albums).

Cary Comes Home 2014 documentation.

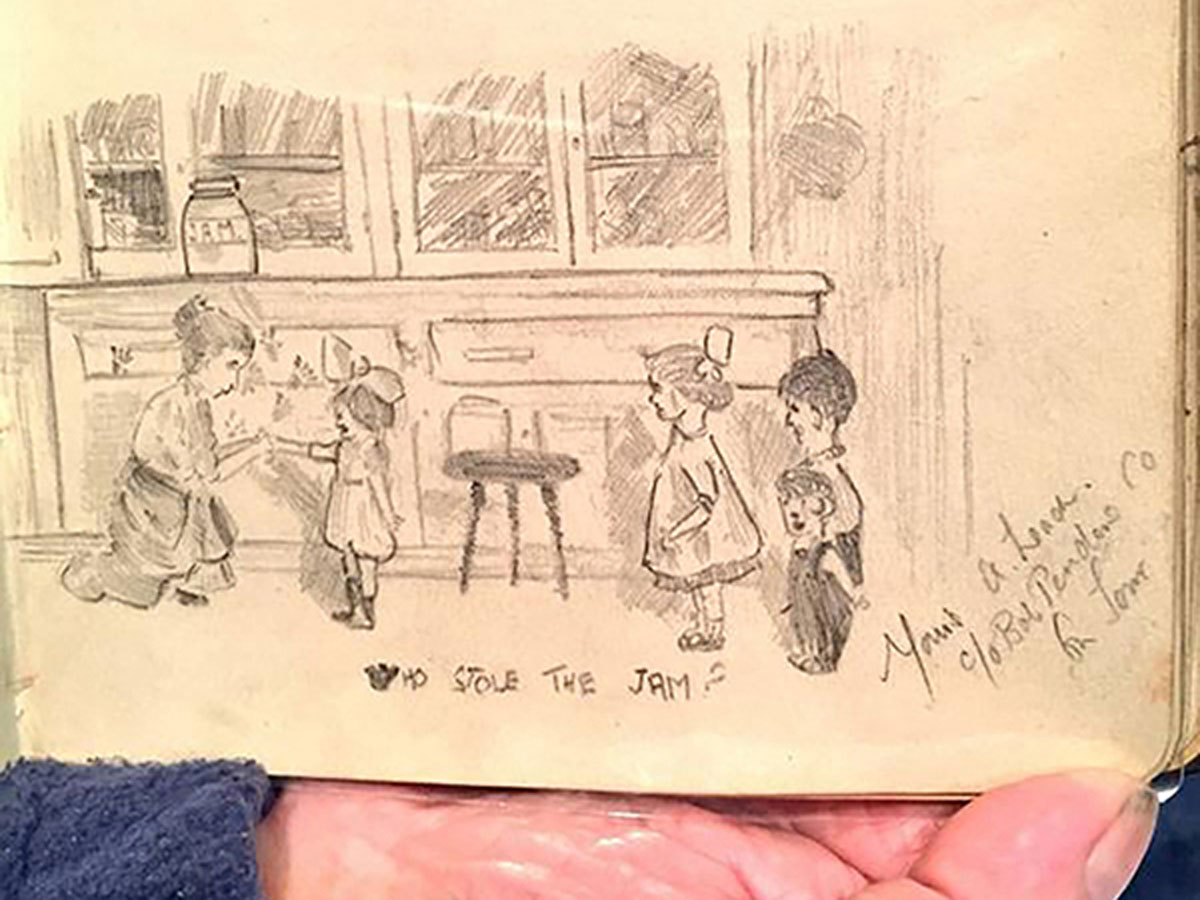

The wider festival catered both for casual tourists by providing light-hearted events – a cocktail party featuring Cary Grant-themed cocktails and his recipe for mushroom canapés – and those looking for more substantial fare: academic panels offering a critical reappraisal of Grant’s stardom, emphasising his Bristol connections, were held at Watershed Cultural Cinema because of its active and influential role in promoting Bristol as a film city (see Presence 2019). In ‘From Horfield to Hollywood’ BBC Radio Bristol presenter Laura Rawlings screened clips from Stuart Napier’s documentary Cary Come Home (2004).10 Members of the audience were invited to share their Cary Grant anecdotes; these included a participant who had a pencil drawing that Archie Leach had sketched at The Empire when he was visiting Bristol on tour with the Penders (see Figure 2).11

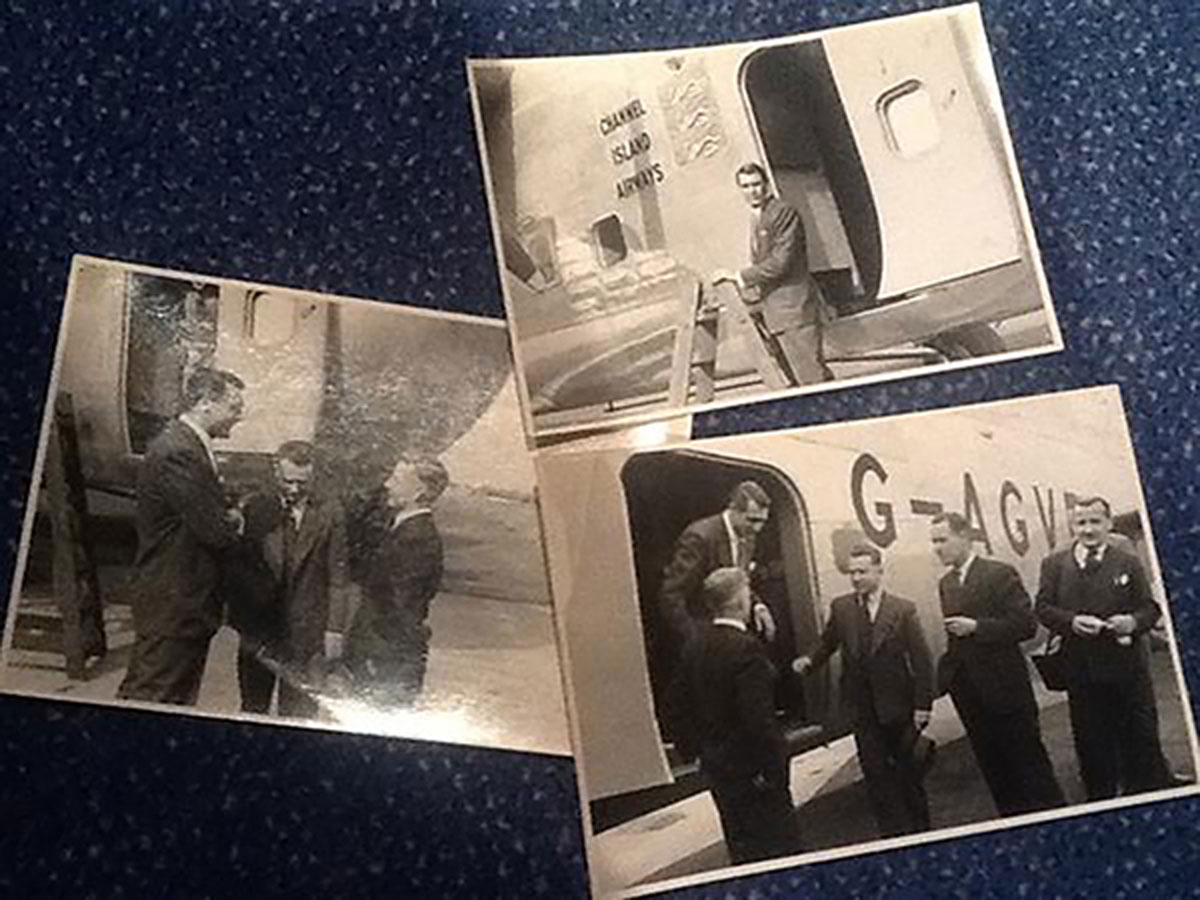

Eve Kellet (94) remembered meeting Grant in the 1960s (see Gearin 2014). Another participant shared images of Grant visiting Filton Airfield (see Figure 3). Capturing these types of local connections are an ongoing feature of the festival.

The 2,000-seater Hippodrome was a risky venue, not only expensive to hire but being a theatre, also lacking inbuilt screening facilities, which meant additional costs of projector, screen and PA hire, on top of the film licence. Our determination to work with the venue because of its compelling association with Cary Grant reveals a tension that has underpinned the festival: between the need to cover costs and the desire to curate his work in new ways. We also learned the difference between hiring a venue and working in partnership with one. When you share the box office, your venue partner has an incentive to drive ticket sales (as happened with Watershed); conversely when you hire a venue simply as a space (as with Bristol Hippodrome, run by national chain, the Ambassador Theatre Group), once they have your hire fee, there is no incentive to support the marketing and promotion.12 However, we also learned that wrap-around content helped to ‘decentre’ the potentially conversative programming choices we had made to attract ticket sales, and tapped into Bristol’s carnivalesque contemporary cinema culture. Although the Hippodrome did not sell out and the festival overall made a financial loss in its first year, it received international recognition (see Murphy 2014, Gearin 2014, ABC News 2014). Above all it was made worthwhile just to stand on the steps of the Hippodrome with Colleen Zwack, a self-described ‘superfan’ from Minneapolis (BBC 2018), overcome with the emotion of having just watched Grant on the big screen in the very venue where he started out, sharing that locative frisson that had propelled me to start the festival in the first place (see Figure 4).

Colleen Zwack on the red carpet at Bristol Hippodrome, October 2014 (BBC Online 2018).

2016 Festival

The second festival (16–17 July 2016) expanded this dispersed festival model by partnering with Bristol Harbour Festival to highlight the importance of seafaring in the symbolic and physical journey from Archie Leach to Cary Grant. This was part of a deliberate strategy to partner with existing events in the city, designed to maximise audience reach. The festival had a pop-up stall in Millennium Square next to the Cary Grant statue, right in the heart of the Harbour Festival, where visitors could imagine they were on the deck of the RMS Olympic (the ocean liner on which Archie emigrated to America), with deckchairs, deck quoits and swing dance workshops with the Bristolettes. The sea-faring theme was picked up by screening An Affair to Remember (dir. Leo McCarey, 1957), which features another transatlantic voyage at the newly renovated Everyman. Established in 1921 as the Whiteladies Picturehouse, the cinema had just reopened in May 2016 after having been closed since 2001.13 This new partnership with Everyman was significant because, as one of Bristol’s oldest extant cinema buildings it is an important landmark in the city’s cinema history and where Elsie Leach would have seen her son’s films when she lived nearby. By curating events there, the festival sought to raise awareness of both Cary Grant’s and Bristol’s screen heritage, building on my previous research and activism around Bristol as a city of film.

The 2016 festival culminated in an expanded gala screening of Bringing Up Baby (dir. Howard Hawks, 1938) in which Susan Vance (Katharine Hepburn) helps palaeontologist David Huxley (Grant) find his brontosaurus bone. This was positioned under the dinosaur exhibit at Bristol Museum, with wrap around content including cocktails, live music from UWE Big Band and the best-dressed competition (see Video 3).

Cary Comes Home 2016 gala.

Critical context for the films screened at the festival was provided by two illustrated talks at Watershed. Kathrina Glitre analysed Grant’s onscreen chemistry with leading ladies such as Deborah Kerr and Jean Arthur, and Mark Glancy offered a detailed production analysis of our gala film.

Although there were several successes, curatorially, the 2016 festival was still finding its voice. Venues were too spread out across the city for such a small team to manage comfortably, and the programming also lacked thematic coherence, failing to capitalise on the Grant-Hawks connection. The choice to work with another non-traditional venue for our gala proved both costly and time-consuming and was not justified by a strong enough connection with Grant. However, despite not receiving any major sponsorship, the festival just managed to break even mainly due to sharing the box-office with cinema venue partners and the festival continued to garner national attention with a write up in The Guardian (Hutchinson 2016).14

Fringe Events

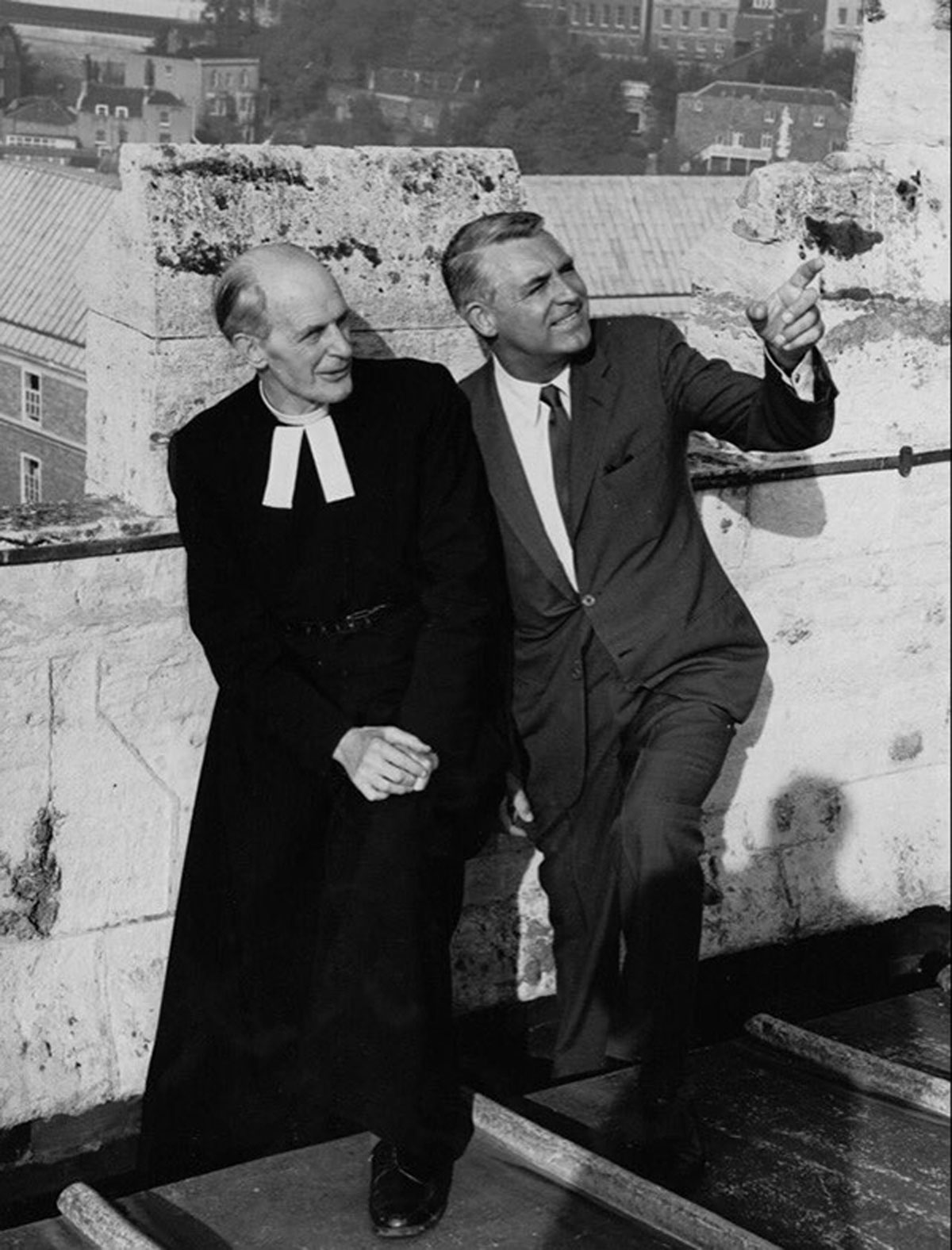

Although the biennial festival weekends were the main vehicle through which Grant’s connection to Bristol was curated, they were augmented by fringe events throughout the festival years and in the intervening years between the festivals.15 From January 2016, these have included partnering with Slapstick, Bristol’s well-established silent comedy festival, Bristol Film Festival and Cinema Rediscovered. One of our most productive partnerships has been with Bristol Cathedral, including birthday and Valentine’s events and a Christmas screening of The Bishop’s Wife (dir. Henry Koster, 1947). The screening, which took place in the main nave, combined all the usual gala trappings, including live music from UWE Big Band and an introduction by Col Needham.16 It was made more resonant by the parallel between the film’s storyline – in which Grant stars as Dudley, a guardian angel sent down to guide newly appointed Bishop Henry Brougham (David Niven) in his struggle to raise funds to build an elaborate new cathedral – and the existence of a photograph of Cary Grant with the Dean of Bristol Cathedral in 1965, which is said to have been a publicity shot to raise funds for its roof (see Figures 5 & 6 and Video 4).

Cary Comes Home 2018 promo.

2018 Festival

Building on the momentum of the Bristol Cathedral partnership, the 2018 festival (23–25 November) was the most successful live iteration to date, financially and curatorially. It was themed primarily around Grant’s enduring relationship with Alfred Hitchcock, the ‘only actor that Hitchcock ever loved’.17 The festival was designed to ensure audiences had a number of different ways of engaging with this well-worn theme, with talks and films, including a gala screening of To Catch A Thief with all the usual wrap around content, at the Trinity Arts Centre in Old Market, near the Empire Theatre where Grant used to work. Although the festival employed what Stringer would call a conservative strategy, invoking an auteur paradigm that was coloured by the ‘weight of the interpretive frames provided at and around such events’ (Stringer 2003: 83), this tactic ensured its financial viability. And its expanded cinema approach offered productive opportunities for decentring, or indeed relocating Grant within his specific Bristol context. In addition, partnering with the Trinity and The Cube Microplex – a community-run cinema in the heart of St Pauls, the area where Cary Grant lived with his grandmother after the loss of his mother – formed part of an overarching strategy to reach a wider, more diverse audience.

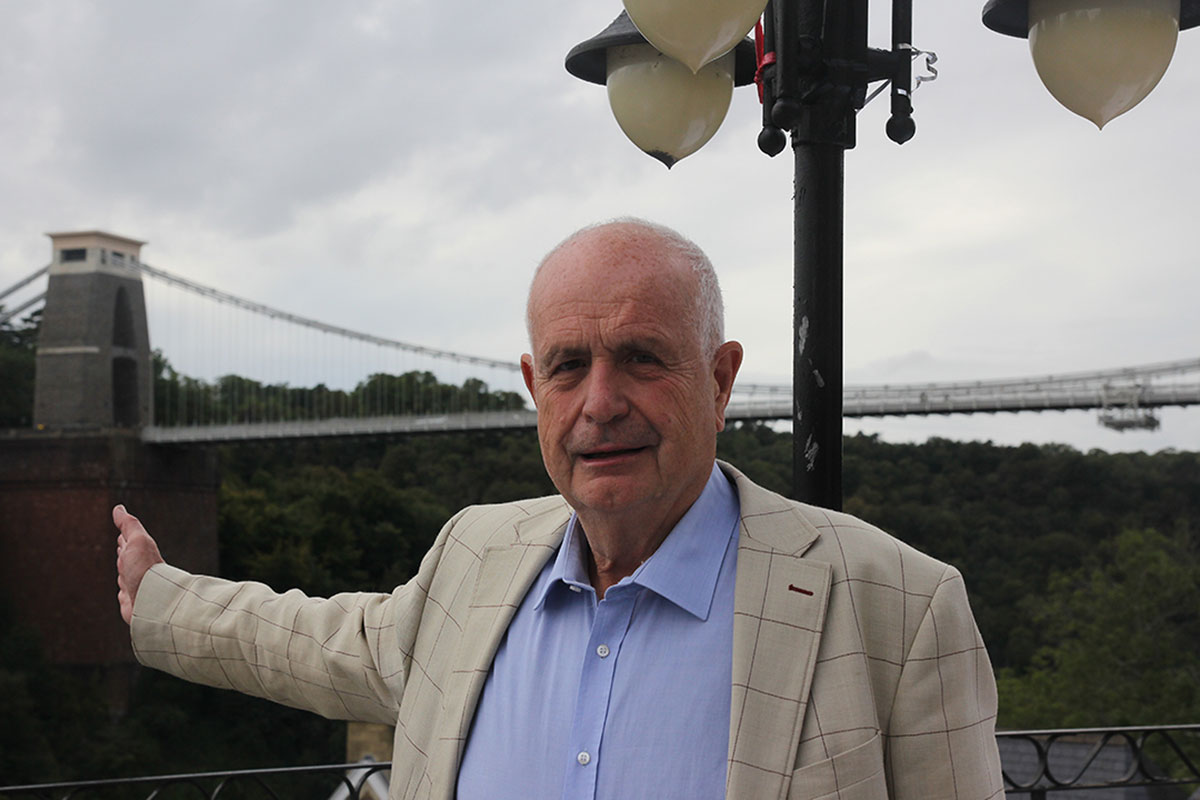

The central aim was to create additional opportunities for participation, the sharing of memories and providing opportunities for fan pilgrimage and deepening the engagement with ‘sacred sites’. This was best illustrated by a ‘Cary Grant in Bristol’ afternoon tea at the Avon Gorge Hotel, which built on the success of our previous ‘Walk and Talk Like Cary Grant’ acting workshop that we’d held there in 2014. Originally known as The Grand Clifton Spa, this is one of the hotels at which Grant used to stay on trips home to Bristol, but could never have aspired to stay at, or even visit, when he was growing up in the city as Archie Leach, thus emphasising the different Bristols experienced by those two selves. Furthermore, the event took place in a function room overlooking the terrace with a view of the Clifton Suspension Bridge designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, where Grant was photographed by Bristol Evening Post (see Figure 7), thus transposing the Hollywood star onto an already iconic Bristol landmark, shifting the discourse from engineering achievements to star charisma.

One of the presenters at our event, David Brown, had briefly worked at the hotel in the 1970s and looked after Cary Grant on one of his many visits, when he was asked to help to set up this iconic photograph. Brown himself and guests were invited to re-enact the photograph in the exact same spot on the terrace (see Figures 8 and 9).

David Brown, recreating the photograph of Cary Grant at the Avon Gorge, which he helped to set up. © Charlotte Crofts 2018.

Recreating the iconic photograph of Cary Grant at the Avon Gorge Hotel overlooking the Clifton Suspension Bridge at Cary Comes Home 2018 © Charlotte Crofts 2018.18

Such recreations of an iconic celebrity image and the place where it is taken, Richard Howells argues, can take on religious significance as a site of fan pilgrimage because of the participants’ ‘physical connection with the person involved’ (Howells 2011: 112, 128). The fan practice of rephotography becomes an act of devotion and ‘re-enacting and photographing at screen tourism locations’ can be used to plan screen tourism destinations (Kim 2010: 60). This insight has informed our marketing of the festival using the #MakeThePilgrimage hashtag and encouraging people to take a #CaryGrantSelfie next to the Cary Grant statue (see Cary Comes Home Twitter (2020)) (see Figure 10).

Cary Grant statue in Millennium Square, Bristol, UK, haloed by the ferris wheel © Charlotte Crofts 2018.

Another such ‘sacred site’ was the venue for a screening of the award-winning documentary Becoming Cary Grant (dir. Mark Kidel, 2017) at the University of the West of England’s Glenside campus, the location of what was originally the Bristol Lunatic Asylum where Grant’s mother Elsie was committed for over 20 years. Elsie’s incarceration had a deep impact on Grant’s trajectory to stardom. Soon after he turned eleven, Archie came home from school to find his mother gone. Perhaps because of the taboo surrounding mental health, or perhaps because it was convenient for his father, Archie was led to believe that she was dead. In reality she had been committed on 3 February 1915 for ‘Mania’ based on the testimony of her husband Elias that she had been ‘queer in the head for some months’ (Bristol Records Office: 40513/Med/C/CB/4/18 & 40513/Med/PR/Ar/1/7). It was only after he had become Cary Grant that Archie learned the truth on a visit home for Christmas in 1933 (Glancy 2020a: 111). Elsie was released on 26 July 1936, just as 32-year-old Grant was reaching the height of his fame (Bristol Records Office: 40513/Med/PR/Ar/3/2).

The film explores Grant’s life from the perspective of his (then legal) LSD therapy sessions in the 1950s, using extracts from his autobiography (spoken by Jonathan Pryce) and home movie footage (much of it shot in Bristol), to piece together a moving account of his journey from Archie Leach to Cary Grant.19

By screening the film at Glenside, the festival sought to honour and contextualise Elsie’s experience with mental illness in the very auditorium where she would have spent her recreational time as a patient (see Figure 11). The film’s formal use of Grant’s LSD therapy as a structuring device through which to explore his biography highlighted the impact that the loss of his mother had on his own mental wellbeing. This was made more poignant by the venue and given critical context provided by the panel discussion, consisting of the film’s director Mark Kidel, Stella Mann (curator Glenside Hospital Museum), neuropsychopharmacologist Professor David Nutt (Imperial College London) and Mark Glancy, who was a consultant and contributor for the documentary. There was a collection for the local mental health charity, Bristol Mind. In this way, the festival could be seen to be humanising Grant by exploring his difficult upbringing, connecting his personal history to the Grant image.

Feedback from participants in the 2018 festival (Crofts 2021a) indicates that it succeeded in offering film tourists various opportunities to ‘commune’ with the object of their veneration, providing ways for Cary Grant fans to worship collectively at the altar of the man from dream city.20 One visitor from Denver Colorado heard about the festival on the Cary Comes Home Facebook Page and was motivated to come by the Hitchcock/Cary Grant theme. Speaking after the ‘Cary Grant in Bristol’ event on the terrace of the Avon Gorge, she said: ‘How can you pass up Alfred Hitchcock and Cary Grant together? You just can’t do it if you are a Cary Grant fan’ (see Video 5). She contacted her friend who agreed to join her, having become fascinated about the relationship between the two during a Turner Classic Movie class, ‘so when she told me about this I really wanted to come and I’m very glad I have.’

Cary Comes Home 2018 vox pops with American visitors.

For both participants, learning about Cary Grant’s Bristol contributed to a ‘transfigured’ understanding of his life in Bristol and the ‘juxtaposition of who he was in life and on film’. The festival’s critical framing of Grant was of central importance in this transformation, expanding patterns of taste, enabling a deeper engagement with his acting skills and participating in a recreation of a vanished era that continues to function as a golden age both of cinema-going and of star charisma, ‘it’s permanently changed how I look at both Hitchcock and Cary Grant when I watch these works again’.

A Bristolian woman who lives near Grant’s birthplace, had an understandably different take. Interviewed after the panel discussion of Suspicion she commented:

I live quite near where Cary Grant was actually born … So, I’ve always been fascinated by the Bristol connection… Any chance to see Cary Grant on a big screen is really worthwhile for me. And listening to people talk about films, don’t always agree with everything they say, but it makes you look at the film again, makes you look more carefully. I notice things. So, it sets off a nice chain of reactions and ideas, so that next time you come back to the film you see it again with a fresh eye.

Another American, ‘superfan’ Colleen Zwack, with whom I’d shared a moment on the steps of the Hippodrome in 2014, and who was returning for the third time, found the festival ‘excellent’ and, contending that Grant’s talent ‘transcends generations,’ appreciated the festival’s work in introducing his films to young audiences. In an interview for the BBC, Zwack looked forward to ‘totally immersing myself in Cary Grant for the weekend’ and identified the quasi-sacred space created by the festival as ‘a way to get a closer connection to Cary. Seeing and being in the actual places that were important to a young Archie Leach and later, Cary Grant, is just something extremely special’ (BBC Online 2018). These reactions indicate the importance of place, the ‘auratic’ experience of ‘being there’, which enhanced the aesthetic power of the encounter with the films and stimulated thinking about the importance of Grant’s Bristolian connections. The festival succeeded in mining the productive tension between the present and the past in which the dualism of ‘Archie’ and ‘Cary’ contribute to the affective experience of fandom. These comments speak to the pull of Grant’s Bristol in terms of cinematic tourism, fandom and pilgrimage, testimony to the longevity and endurance of Grant’s star image (Bolton and Wright 2016), enabling different constituencies to engage with his films and his star persona in new ways.

Cary Comes Home’s Role in Bristol becoming a City of Film

Cary Comes Home also functions within the gradual rebranding of Bristol as a city of culture on the international stage. The festival formed part of Bristol City Council’s successful bid to be designated as a UNESCO City of Film, awarded in October 2017. The designation is permanent (unlike the year-long European City of Culture award) and enables Bristol to participate in the Creative Cities Network (UCCN), which aims to strengthen global cooperation on creativity, cultural industries and heritage to make cities more inclusive, resilient and sustainable through local level initiatives, politics and projects. As a member of the UCCN Film Cities sub-network, Bristol has created a four-year Action Plan that aims to increase diversity of local access and engagement with film heritage and culture to help promote social inclusion, gender equality and the participatory governance of urban policies. Cary Comes Home thus contributes to Bristol’s cultural ecology that includes a flourishing production industry (anchored by Aardman Animations and the BBC Natural History Unit), its independent exhibition sector (The Watershed and The Cube) and other film festivals (notably Brief Encounters Short Film and Animation Festival, Afrika Eye, and Wild Screen which programmes natural history films). This rebranding encourages tourism – Aardman has been particularly active through its Wallace & Gromit and Shaun the Sheep city trails – and Cary Comes Home Festival features in Destination Bristol’s presentations to international tourist agencies (Davis 2017). By reclaiming Grant’s Bristol roots, the festival enhances his value to inward tourism – featuring on the Visit Bristol website (no date), Visit Britain (no date) and Ryanair (no date) as one of the best festivals in Bristol/top reasons to visit Bristol – and his outward role as an ambassador for the city. According to Bristol City Council the festival ‘continues to contribute to Bristol’s cultural profile nationally and overseas’ (2020).

In November 2017, a Cary Grant weekend in Bristol’s twin city, Hannover, formed an important part of the 70th anniversary celebration of the two cities twinning in 1947 after the Second World War (see Figure 12). The event’s brochure (Figure 13) featured the iconic Evening Post image of Grant on College Green (Figure 1), as its key image, locating the roots of his international stardom in Bristol.

2020 and Future Plans

2020 events focussed on the theme of ‘journeys’, celebrating the centenary year of Archie emigrating to America: a decisive moment in his life. Activities marking the actual anniversary were due to take place in New York in July 2020, foregrounding this international dimension. Its centrepiece was a one-day symposium addressing this theme at The Graduate Center, City University New York (CUNY), located opposite the Empire State Building, an iconic landmark in An Affair To Remember (1957). There were additional talks and screenings raising awareness of Grant’s New York connections, in partnership with Film Forum and Film Lincoln – two of New York’s most significant cultural centres for film. We had planned to meet on Pier 59 to greet Archie’s arrival on the RMS Olympic at dawn (Eastern Daylight Time) on 28 July. Although live events in New York were cancelled due to Covid-19 restrictions, the festival responded to these exigencies by hosting a series of webinars live streamed to Facebook.

These events aimed to find creative ways to engage audiences and raise awareness of Archie’s long journey from Bristol to Hollywood, via years of hard graft touring America on the Vaudeville circuit, then in musical theatre in St Louis and New York, emphasising the dedication that went into constructing his star persona across several genres, as explored in James Naremore’s online symposium keynote, ‘Some Versions of Cary Grant’ (2020).21 In ‘Sailing With Cary Grant’, I captained the RMS Olympic on the centenary of Archie’s departure from Southampton on 21 July 1920, thereby locating his first transatlantic voyage in relation to his experiences growing up in a port town and his aspirations to both international travel and stardom (see Crofts 2020a). In ‘Greeting Cary Grant’, I piloted the Olympic into Pier 59 using Google Earth, virtually mapped significant locations in New York using Google Maps, and then used Street View to see the interior of the theatres at which he had performed (Crofts 2020b). Whilst we would much rather have been there, these online events were perhaps better attended than a physical event would have been with participants from all over the UK and the rest of the world, including America, China, Australia and mainland Europe.22 Encouraged to use the hashtag #CaryNY100, some participants really got into the spirit of the ‘journey’ theme; two New Yorkers even dressing the part (see Figure 14).

Due to the pandemic, the fourth Cary Comes Home Festival (20–22 November 2020) took place entirely online using Crowdcast and Zoom to host illustrated talks, introductions to watch-along screenings, panel discussions and a Cary Grant quiz in partnership with Twentieth Century Flicks, Bristol’s iconic video shop.23 The festival developed the theme of journeys in a number of ways, not only celebrating Archie’s emigration to the Big Apple in 1920, but also acknowledging other journeys of class and social mobility, identity and self-discovery. As part of this theme, the festival partnered with the Video Essay Podcast to invite video essays on the theme of The Journeys of Cary Grant (DiGravio 2020), which culminated in a panel discussion with the filmmakers live at the festival which was later aired as a podcast. Our gala film was An Affair to Remember (1957) which is set on a transatlantic cruise, but also explores several other kinds of mobility. This inspired the ‘Love Affairs to Remember Marathon’, which ended with a panel discussion with Ross Wilcock on the representation of dis/ability. Two illustrated talks sought to extend understanding of the impact of growing up in Bristol had on Grant’s trajectory to stardom and how his image still circulates globally today (Glancy 2020b and Crofts 2020c). Throughout the festival, we attempted to create a sense of togetherness in isolation, using the hashtag #CaryStaysHome and inviting interaction in the chat and on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

As argued above, the aims of the festival hinge on the embodied, haptic, located experience of attending in person, drawing on my previous locative cinema apps. The festival’s stimulus to cinematic tourism and pilgrimage and the importance of place and ‘emplacement’ are pivotal. However, whilst online events obviously cannot emulate the experience of meeting ‘in real life’, audience feedback suggests that they were nevertheless seen to create a sense of communitas during lockdown with a feeling of connection with both Cary Grant fans and cinephiles. One attendee claimed: ‘It made me feel apart (sic) of a wonderful community … Excited to meet fellow fans of Cary Grant’ (2021a: 103). Another reported feeling ‘less isolated’ (2021a: 103). Many participants appreciated the ‘imaginative virtual programme to replace planned activities’ (2021a: 65), which provided ‘welcome cheer during a difficult lockdown year’ (2021a: 84).

The online festival attracted new audiences with 53% attending the November 2020 Festival for the first time (2021a: 85). However, some attendees had attended previous Cary Comes Home events going back until 2014 and these ‘regulars’, reported enjoying the experience of meeting old friends and making new ones. Being online meant a wider geographical spread of attendees who did not have to travel. According to data taken from Eventbrite and Crowdcast analytics, many attendees came from English-speaking countries such as America, Canada and Australia, mainland Europe, and Central and South America and Asia (2021a: 107).

Although less effective/affective than meeting in real life, the success of these online events suggests that it is possible to create a sense of communitas and pilgrimage in the virtual realm and that watching together even if physically separate can contribute to a feeling of co-presence and being connected to a wider film community. Furthermore, the benefits of online events for accessibility and environmental sustainability are also significant. Going forward, the challenge will be whether a blended approach to festival programming might emerge as a way to capture the best of both worlds, so that we can meet in the real world when it safe to do so, yet still remain accessible to a wider audience. Future avenues of research might include a more detailed analysis of our audience demographics, thinking about how to bring the festival to a more diverse audience, as well as a qualitative analysis of audience feedback that would evaluate how the festival contributes to wellbeing, alleviating social isolation and creating community cohesion.24

Concluding Reflections

As this article has elaborated, Cary Comes Home has contributed to Bristol’s rebranding as a film city in which Grant’s iconic power acts as a cultural ambassador for the city’s film heritage. It has also helped to shift the discourse around his star image so that a deeper understanding of his regional identity – rather than just his national identity – becomes an important part of the way in which we think about the complexities, contradictions and instabilities of that star persona. For example, where earlier works on Grant do not navigate the nuances of his Bristol upbringing, Glancy’s (2020b) recent biography contains ground-breaking revelations about the levels of poverty in his family history and critical reflection on how the specific cultural geographies of Bristol inflect Archie’s trajectory.25 The festival’s curatorial approach has also impacted on the national conversation. According to the BFI (2020), the Cary Comes Home Festival had a ‘key effect’ on the development, nationally, of the British Film Institute’s highly successful two-month retrospective (August-September 2019). As the publicity for the BFI Southbank Cary Grant Season attests: ‘Despite being seen as quintessentially American’ the blurb points up the fact Grant was ‘born in Bristol and maintained a strong relationship with the UK throughout his life,’ the place ‘where he learned his craft in the world of variety, acrobatics and slapstick’ (BFI 2019).26 This is in contrast to a previous NFT Season (1 Sept – 7 Nov 2001), which predominantly marketed Grant as ‘The Man From Dream City’, firmly locating him as a Hollywood star. It can be argued, therefore, that Cary Comes Home has changed the perception of Grant, locally, nationally and internationally, contributing to a deeper understanding of his Bristol roots, together with helping to place Bristol’s screen heritage on the global map.

What I also hope to have demonstrated in this article is the potential for similar projects that resituate and, in the process, redefine star personae. The discussion has shown the importance of expanded cinema and a dispersed approach to festival curation, working with local partners to enable audiences, including fan ‘pilgrims’, to engage with Grant’s films in new and often more meaningful ways. Although ambitions to expand taste horizons always need to be tempered by consciousness of costs, I suggest that imagination and a degree of curatorial acumen rather than a major financial investment is the key to achieving success.

Notes

- This dualism and its relation to the construction of Grant’s star persona is recognised in the titles of two recent biographies, Scott Eyman’s (2020) Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise and Mark Glancy’s (2020) Cary Grant, The Making of a Hollywood Legend. [^]

- The Cary Comes Home Festival would not have been possible without the groundwork of David Long, who successfully campaigned to erect the Cary Grant statue which now stands in Millennium Square in the heart of Bristol. Whilst Long’s work to memorialise Grant in Bristol did not lead directly to the Cary Comes Home Festival, the festival built on his achievements. [^]

- According to Glancy ‘When he returned to Bristol twenty-five years later, he revisited this old haunt and filmed it with his own 16mm movie camera’ (2020: 19), a testimony to the importance of Archie’s Bristol cinema-going experiences. [^]

- Devil and the Deep (1932) – screened 10–15 July 1939; Blonde Venus (1932) – screened 3–8 April 1933; Hot Saturday (1932) – screened June 5–10, 1033; Alice in Wonderland (1933) – screened twice: December 31, 1934–January 5, 1935 and December 30, 1935–Jan 4, 1936; Born to be Bad (1934) – screened October 29–November 3, 1934; The Amazing Quest of Ernest Bliss (1936) – screened December 28, 1936–Jan 2, 1937 (Shorney 2012). [^]

- The newspaper had an arrangement with Grant to have an exclusive photoshoot if they left him alone for the rest of his visit. See Figures 1 & 7 courtesy of Bristol Post. [^]

- This was taken in the summer of 1957, his first visit home for 5 years (Glancy 2020: 346), as the Council Building (now City Hall) was not erected until April 1956. [^]

- In her discussion of the ‘curatorial potential’ of film festivals, Rastegar argues that whilst the ‘concept of curating has become an increasingly chic way of describing any form of selection that shows off taste,’ its etymology derives from the Latin “to care” and the eighteenth-century clerical meaning of “curate” as a ‘spiritual guide responsible for the care of souls’ (2016: 182). [^]

- This included partnerships with Hippodrome Backstage Theatre Tours and the Bristol Insight open-top bus tour of Bristol, both of which ran special versions of their existing tours with a Cary Grant emphasis (see Cary Comes Home Website). [^]

- In addition, we ran a filmmaking competition for the best short film inspired by North by Northwest. Shortlisted entries were screened on the Big Screen in Millennium Square next to the Cary Grant statue and the winners were announced before the second screening (see Video 2 and Cary Comes Home Website). Both additions aimed to use Cary Grant’s life and work as a spur to creativity for contemporary young performing artists and filmmakers. [^]

- This documentary was produced by David Long and first screened at Grant’s 100th birthday event at Watershed in 2004. [^]

- Rawlings had called for contributions from people who had met or knew Grant on her radio show. Working with a local radio host was a deliberate strategy to engage with a wider regional audience in this first year and has continued to inform marketing strategy, extending to national radio (BBC Front Row 2018 and BBC Free Thinking 2020, with Matthew Sweet). [^]

- The 2014 festival would not have been possible without one-off sponsorship from UWE Bristol which enabled us to take the financial risk and the support of Watershed as venue partner, which has been ongoing. [^]

- I was involved in the campaign to save the cinema (BBC 2013), it was also the location of my first cinema-going experience (Crofts 2021c) and featured in my Cinemapping prototype as part of the City Strata AHRC REACT Project (Crofts 2012c). [^]

- It was at this juncture that Anna Farthing stepped down from the festival due to its financial precariousness. Since 2017 the core team has consisted of Festival Director Charlotte Crofts, Festival Coordinator Fern Dunn and Festival Assistant Julia Moorish. [^]

- Space constraints mean that only some of the activities can be mentioned here. See the Cary Comes Home Website for a full archive of events. [^]

- This event was supported by a generous donation from Col Needham, Founder and CEO of Bristol-based IMDb.com and major Cary Grant fan, attracting our largest audience since the Hippodrome in 2014. [^]

- Hitchcock also has a Bristol connection, an avid wine-collector, he visited Bristol to buy wine from Averys Wine Merchants as evidenced in a letter to the proprietor Ronald Avery (BBC 2018a). [^]

- Apologies for the low resolution of this image which, although not a selfie, was taken on a phone. [^]

- The festival contributed to the development of the documentary in several ways: producer Nick Ware interviewed contributors at the 2014 festival for the pilot and Glancy was subsequently engaged as a consultant and contributor for the film. Cary Comes Home Festival and Crofts are acknowledged in the end credits of the film (Ware 2020). We hosted a preview and a director Q&A, showing extracts from work in progress in 2016 and partnered with Watershed for the documentary’s English premier at the inaugural Cinema Rediscovered Festival in July 2017. [^]

- The festival was extensively promoted by the local press: lifestyle magazine Bristol Life featured it on their cover, with an editorial and six-page spread (Robins 2018a: 3, 2018b: 26–31); it was also featured on the cover of The Bristol Magazine accompanied by an article by the festival director (Crofts 2018); as well as featuring on BBC Online (2018b). [^]

- See also Naremore’s seminal chapter Acting in the Cinema on Grant’s performance in North by Northwest (1988: 213–35). [^]

- Not flying to New York also clearly reduced our carbon footprint and so has implications in relation to addressing the environmental impact of film tourism (see Kim et al 2017). [^]

- We were unable to stream films online due to distribution rights, so participants had to source their own copy of the films and ‘watch-along’ at home, drawing inspiration from Carol Morley’s #FridayFilmClub on Twitter during the first lockdown. We met on Crowdcast for a brief introduction and a countdown to pressing play. [^]

- This was the subject of a recent presentation ‘Keep Calm and Cary Online’ at BAFTSS 2021 Annual Conference (Crofts 2021b). [^]

- Glancy acknowledges the impact of the festival on his research ‘While writing, I also became involved with the wonderful Cary Grant Festival, also known as Cary Grant Comes Home for the Weekend, which was founded in Bristol in 2014 and has been held biennially since then. Dr. Charlotte Crofts, the tireless festival director, brings together experts and enthusiasts from around the world for these festivals. I have learned a great deal from attending them and from giving talks alongside Kathrina Glitre and Andrew Spicer’ (2020: xviii). [^]

- The Cary Comes Home Festival was acknowledged in the season brochure, and I was invited to introduce the season, entitled ‘Cary Grant: From Knockabout to Knockout’, which aimed to raise awareness of Grant’s Bristol roots, and how they informed his trajectory from ‘son of a tailor’s presser’ to ‘global film star and style icon, whose image still circulates as the epitome of elegance today’ (BFI 2019). [^]

Ethics and Consent

This research has the full ethical approval of the Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education Research Ethics Committee, reference: UWE REC REF No. ACE.20.11.027.

Acknowledgements

I would especially like to thank Andrew Spicer for substantial editorial contributions in the writing of this article and Paula Rainey Crofts for her unfailing support and beady eye. I would also like to thank (in alphabetical order) Pam Beddard, Eugene Byrne, Mark Cosgrove, Kathryn Davis, Fern Dunn, Anna Farthing, Mark Glancy, Kathrina Glitre, Alix Hughes, Pamela Hutchinson, Justin Johnson, Andrew Kelly, Mark Kidel, Stella Mann, Naomi Miller, Natalie Moore, Julia Moorish, James Naremore, Col Needham, Maddy Probst, Gary Shapiro, Matthew Sweet, Estella Tincknell, Nick Triggs UWE Moving Image Research Centre, UWE students and colleagues, Nick Ware, Colleen Zwack and most of all my family.

Competing Interests

Charlotte Crofts is director of the Cary Comes Home Festival.

References

ABC News. 2014. Cary Grant festival in Bristol – staff get into the spirit. ABC News, 18 October. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-10-19/staff-at-hippodrome/5824610?nw=0 [Last accessed 10 October 2020].

BBC. 2013. Whiteladies Picture House Campaign Halfway to Funding Target. BBC Online, 23 July. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-23021869 [Last accessed 9 October 2020].

BBC. 2018. Bristol Cary Grant film festival celebrates third year. BBC Online, November 23. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-46178044 [Last accessed on 20 July 2019].

BBC Free Thinking. 2020. Cary Grant. BBC Radio 3, 29 April. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000hn1z [Last accessed 11 October 2020].

BBC Front Row. 2018. Cary Grant and Notorious. BBC Radio 4, 9 August. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0007dkh [Last accessed 11 October 2020].

Beeton, S. 2010. The advance of film tourism. In: Tourism and Hospitality Planning and Development. February, 7(1): 1–6. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14790530903522572

BFI. 2019. Cary Grant Season Brochure, August.

BFI. 2020. Impact Testimonial.

Bolton, L and Wright, JL. (eds.) 2016. Lasting Screen Stars: Images That Fade and Personas that Endure. London: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-40733-7

Bristol City Council. 2020. Impact Testimonial.

Bristol Records Office: 40513/Med/C/CB/4/18 (previously 40513/C/3/21) Female Case Book Vol 1/28/139.

Bristol Records Office: 40513/Med/PR/Ar/1/7 (previously 40513/R/5/8) Index of Admissions 1914–1921.

Bristol Records Office: 40513/Med/PR/Ar/3/2 (previously 40513/R/10/10) Registered Discharges and Deaths 1931–1976.

Brooks, X. 2001. Cary Grant country. The Guardian, Aug 17. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/aug/17/artsfeatures [Last accessed on 11 March 2020].

Cary Comes Home Facebook. 2020. Available at http://www.facebook.com/carycomeshome [Last accessed on 11 March 2020].

Cary Comes Home Twitter. 2020. Available at http://www.twitter.com/carycomeshome [Last accessed on 11 March 2020].

Cary Comes Home Website. 2020. Available at http://www.carycomeshome.co.uk [Last accessed on 11 March 2020].

Cohn, A. 1976. Cary Grant: still the cream of Bristol. The Los Angeles Times, January 11: 27–9.

Crofts, C. 2011. Technologies of seeing the past: The Curzon Memories App. In: Dunn, S, et al. (eds.), Proceedings of EVA London 2011: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, 163–170. London: BCS: The Chartered Institute for IT. DOI: http://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2011.29

Crofts, C. 2012a. The Curzon Memories App. IOS and Android smartphone application.

Crofts, C. 2012b. Curzon Memories App. Award-winning poster presented at MeCCSA 2012 Annual Conference, University of Bedford, January. Available at https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/950454 [Last accessed 31 March 2021]

Crofts, C. 2012c. City Strata. REACT Heritage Sandbox. Available at http://old.react-hub.org.uk/heritagesandbox/projects/2012/city-strata/ [Last accessed 9 October 2020].

Crofts, C. 2013a. City Strata: Locative Experience Design and Large-Scale Heritage Apps. Poster presented at MeCCSA 2013 Annual Conference, Derry. Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/drcrofts/city-strata-locative-experience-design-and-large [Last accessed 11 May 2021].

Crofts, C. 2013b. The Lost Cinemas of Castle Park. IOS smartphone application.

Crofts, C. 2018. Cary Grant: More Than Meets the Eye. The Bristol Magazine. Available at https://thebristolmag.co.uk/cary-grant-more-than-meets-the-eye/ [Last accessed 11 October 2020].

Crofts, C. 2020a. Sailing with Cary Grant Cary Comes Home Festival 21 July https://vimeo.com/440467542 [Last accessed 26 sept 2020].

Crofts, C. 2020b. Greeting Cary Grant Cary Comes Home Festival 28 July https://vimeo.com/442347782 [Last accessed 26 Sept 2020].

Crofts, C. 2020c. His Master’s Voice; Cary Grant, Nipper and the Bristol Burr at Cary Comes Home Festival, 20 November.

Crofts, C. 2021a. Cary Grant Comes Home Festival Events Feedback. UWE Research Repository. Available at: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/OutputFile/7094711 [Last accessed 10 May].

Crofts, C. 2021b. Keep Calm and Cary Online: Cary Comes Home Festival and Online Film Culture During the Pandemic. BAFTSS Annual Conference, University of Southampton, 9 April. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h9vXLaTwBAw [Last accessed 9 May 2021].

Crofts, C. 2021c. The transmission of divine light. In: Kelly, M (ed.), Opening Up The Magic Box: Friese-Greene and Reflections on Film, 97–100. Bristol: Bristol Ideas.

Davis, K. 2017. Itinerary: On the Bristol Oscars trail… Visit Bristol Website, 20 Feb. Available at: https://visitbristol.co.uk/blog/read/2017/02/itinerary-on-the-bristol-oscars-trail-b418 [Last accessed 13 October 2020].

de Valck, M. 2007. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. 1st edition. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9789048506729

DiGravio, W. 2020. The Journeys of Cary Grant: An Audiovisual Celebration – Full Screening and Q&A, Vimeo. Available at: https://vimeo.com/481931308 [Last accessed 10 May].

Eliot, M. 2005. Cary Grant: A Biography. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Eyman, S. 2020. Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Film Festival Research Network. 2019. Website. Available at http://www.filmfestivalresearch.org/ [Last accessed 1 October 2020].

Flores Ruiz, D. 2015. Film tourism and local economic development: The Festival of Cinema of Huelva. Cuadernos de Turismo, 36: 461–463. DOI: http://doi.org/10.6018/turismo.36.230931

Flores Ruiz, D, López, CS and González, MDLO Barroso. 2017. The demand of film tourism of festivals: The case of the Festival of Latin-American Cinema of Huelva. The Geographic Notebooks, 56(2): 245–262.

Gearin, M. 2014. Who would’ve known Cary Grant was born in Bristol? ABC News, 19 October. Available at https://abcmedia.akamaized.net/news/audio/cr/201410/20141018-cr03-bristolson.mp3 Transcript available at https://www.abc.net.au/correspondents/content/2014/s4109840.htm [Last accessed 10 October 2020].

Glancy, M. 2020a. Cary Grant, The Making of a Hollywood Legend. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190053130.001.0001

Glancy, M. 2020b. “Roamed About Again”: Cary Grant’s Wanderlust at Cary Comes Home Festival, 20 November.

Grant, C. 1963. Archie Leach. Ladies Home Journal, Part 1, January/February; Part 2, March; Part 3, April. Available at http://www.carygrant.net/autobiography/ [Last accessed on 11 March 2020].

Howells, R. 2011. Heroes, saints and celebrities: the photograph as holy relic. Celebrity Studies. 2(2): 112–130. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2011.574866

Hutchinson, P. 2016. Cary Grant: From the Bristol docks to the Hollywood hills, The Guardian 8 July. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2016/jul/08/cary-grant-festival-bristol-hollywood-film [Accessed 5 September 2021].

Kael, P. 1975. The man from dream city. The New Yorker, July 7. Available at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1975/07/14/the-man-from-dream-city [Last accessed 5 October 2020].

Kidel, M. 2017. Becoming Cary Grant. Yuzu Productions for Showtime.

Kim, S. 2010. Extraordinary Experience: Re-enacting and Photography at Screen Tourism Locations. Tourism and Hospitality Planning and Development, 7: 1, 59–75. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14790530903522630

Kim, S, Kim, S and Oh, M. 2017. Film Tourism Town and Its Local Community. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 18(3): 334–360. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2016.1276005

Macionis, N. 2004. Understanding the film-induced tourist. In: Frost, W, Croy, G and Beeton, S (eds.), Proceedings of the International Tourism and Media Conference. Melbourne, 86–97. Australia: Tourism Research Unit, Monash University.

Macionis, N and Sparks, B. 2009. Film tourism: An incidental experience. Tourism Review International, 13(2): 93–102. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3727/154427209789604598

McCann, G. 1996. Cary Grant: A Class Apart. London: Fourth Estate.

Murphy, P. 2014. From Bristol to Hollywood and Back – Cary Grant Comes Home for the Weekend, Huffington Post, 21 November. Available at https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/paul-murphy/from-bristol-to-hollywood_b_6198464.html [Last accessed 10 October 2020].

Napier, S. 2004. Cary Come Home. 123 Media for ITV West. Produced by David Long.

Naremore, J. 1988. Acting in the Cinema. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/9780520910669

Naremore, J. 2020. Some versions of Cary Grant. Cary Comes Home Festival 28 July. Available at https://vimeo.com/442473720 [Last accessed 26 Sept 2020].

Presence, S. 2019. “Britain’s first media centre”: A history of Bristol’s Watershed cinema. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 39(4): 803–831. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2019.1600905

Rastegar, R. 2016. Seeing differently: the curatorial potential of film festival programming. In: de Valck, M, Kredell, B and Loist, S (eds.), Film Festivals History, Theory, Method, Practice, 181–195.

Robins, D. 2018a. Editor’s Letter. Bristol Life, Issue 255, 16 Nov, p. 3. Available at https://issuu.com/mediaclash/docs/brl255_final [Last accessed 11 October 2020].

Robins, D. 2018b. Smooth Operator. Bristol Life, Issue 255, 16 Nov, 26–31. Available at https://issuu.com/mediaclash/docs/brl255_final [Last accessed 11 October 2020].

Ryanair. no date. Top Festivals to Visit in Bristol. Ryanair. Available at https://www.ryanair.com/try-somewhere-new/ie/en/travel-guides/top-festivals-to-visit-in-bristol/?sub1=20201010-1552-039d-8ba2-0c636131ed47 [Last accessed 9 Oct 2020].

Shorney, J. 2012. Celebrating 100 years of Bristol Hippodrome, 1912–2012. Archived on the Internet Archive. Available at http://web.archive.org/web/20121215031431/http://www.hippodromebristol.co.uk/1930-1939.html [Last accessed on 11 March 2020].

Stringer, J. 2003. Raiding the archive: film festivals and the revival of Classic Hollywood. In: Grainge, P (ed.), Memory and popular film, 81–96. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt155jfm0.9 [Last accessed 26 September 2020].

Tzanelli, R. 2004. Constructing the ‘cinematic tourist’: The ‘sign industry’ of The Lord of the Rings. Tourist Studies, 4(1): 21–42. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1468797604053077

Tzanelli, R. 2010. The Da Vinci node: Networks of neo-pilgrimage in the European cosmopolis. International Journal of Humanities, 8(3): 113–128. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9508/CGP/v08i03/42874

Thomson, D. 2014 [1975]. The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, 6th edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Urry, J and Larsen, J. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. London: Sage. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4135/9781446251904

Visit Bristol no date The Best of Bristol – discover the city’s Oscar-Winning connections. Available at https://visitbristol.co.uk/blog/read/2016/02/the-best-of-bristol-discover-the-citys-oscar-winning-connections-b241 [Accessed 5 September 2021].

Visit Britain no date 8 Reasons to Visit Bristol Before the Year Ends. Visit Britain. Available at https://www.visitbritain.com/au/en/8-reasons-visit-bristol-year-ends-0 [Last accessed 9 October 2020].

Ware, N. 2020. Impact Case Study Testimonial. Unpublished.