Introduction: the audio-visual essay and communicative exchange

In The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film, Laura Rascaroli (2009) argues that one of the defining characteristics of the audio-visual essay is that it is based on a structure of ‘communicative negotiation’. The essayistic text, she argues, foregrounds the ‘enunciational subjectivity’ of its creator so that it may establish a substantial ‘dialogue between filmmaker and spectator’ (2010: 3–7). As opposed to effacing the role that the filmmaker has played in shaping the cinematic text, the audio-visual essay foregrounds the layers of mediation that separate the referent from its filmic record. As Rascaroli (2009: 36) continues, the audio-visual essay ‘reflects on its own coming into being, and incorporates in the text the act of reasoning itself’, and in the process, calls upon the spectator to ‘engage in a dialogical relationship with the enunciator, hence to become active, intellectually and emotionally, and interact with the text’. The cinematic essayist, therefore, draws the viewer’s attention to their role as the guiding authorial figure who consciously manipulates sounds and images to construct essayistic discourse.

It is the contention of this article that there is a notable and curiously under-explored connection between the impulse towards dialogism in the audio-visual essay, on the one hand, and the capacity for digital technologies to create interactive viewing situations that collapse the gulf that separates media ‘producer’ from media ‘consumer’ in traditional paradigms of screen spectatorship, on the other. As D.N. Rodowick (2007: 177) argues, in an era where the vast majority of images are produced, stored, distributed and accessed through computer technologies, ‘the spectator is no longer a passive viewer yielding to the ineluctable flow of time, but rather alternates between looking and reading as well as immersive viewing and active controlling’. It is understandable, then, why so many essayistic filmmakers have utilised the two-way functionality of the computer system as a means to empower the ambulatory gaze of the viewer by enabling them to directly alter the temporality, structure, and design of the text. To investigate how strategies of articulating the authorial voice and immersing the viewer in a process of communicative exchange have transformed through engagement with the dialogical potential of new media, I will focus on the late work of Chris Marker, and, in particular, his digitally composed audio-visual essays Immemory (1997) and Ouvroir (2012).

This article offers two substantial contributions to existing scholarship: firstly, it demonstrates the impact of digital technology on the nature of spectatorial engagement in essayistic audio-visual texts; secondly, it explores the role that technological innovation played in facilitating communicative exchange between filmmaker and spectator across Marker’s body of work. In this article, I demonstrate that Marker has embraced the possibilities of digital filmmaking technology in a particularly vigorous and dynamic way to allow his viewers to play an active role in the construction of essayistic meaning. Applying close textual analysis to two hugely innovative works of Marker’s late period, I show that Marker’s utilisation of digital media is rooted in the tradition of the literary essay, dating back to Montaigne, which has longed to foster a dynamic relationship of communicative negotiation between the text and the audience. For Marker, the reflexivity of the essay is not a solipsistic exercise but a means of facilitating the participation of the viewers, allowing them to share in the essayist’s tentative and sceptical exploration of their own epistemological strategies. If essaying has always been a dialogical endeavour for Marker, fundamentally concerned with a dynamic exchange between himself, his subjects, and his audience; then the two-way, return-channel infrastructure of the digital interface, I argue, has enabled him to establish interactive spaces of textual negotiation.

At this point, a brief note on terminology is necessary. This article employs the term’ audio-visual essay’, instead of the commonly used labels ‘essay film’ or ‘video essay’, to highlight my conception of the ‘essay’ as an artistic form that is not bound to any single technological medium. Considering that this article focuses on an artist who has produced a variety of essayistic works in film, electronic video and digital, the broader term’ audio-visual essay’ is more suitable than a term which carries connotations of any specific technical mode of cinematic production. The issue of how an ‘essay’ may be theorised as a cinematic form is a contentious one, and a great deal of recent scholarship has been dedicated to determining its generic position within the history of non-fiction cinema. Despite the recent increase in interest in the form amongst academics and journalists, there is still no clear critical consensus on how exactly the audio-visual essay may be defined or even on whether there is enough of a difference between the audio-visual essay and other branches of nonfiction cinema to warrant it being discussed as a separate subcategory. The sense of uncertainty regarding how to categorise the essay is not only limited to film studies – literary critics have struggled to define the essay in its written form for centuries. As Réda Bensmaïa (1987: 99) writes: ‘No other genre ever raised so many theoretical problems concerning the origin and definition of its Form: an atopic genre or, more precisely, an eccentric one insofar as it seems to flirt with all the genres without ever letting itself be pinned down’. Some critics have gone so far as to claim that the ‘essayistic’ is not a distinct artistic mode, and that critics only latch on to it in a lazy attempt to lump together a diverse range of texts that resist easy classification. For example, Andrew Tracy (2013), reacting to the frequent use of the term ‘essay’ in contemporary film criticism, argues that the phrase is ‘taxonomically useful’ for critics seeking to ‘define a field of previously unassimilable objects’ across cinema history, but, as a form of filmmaking, it is ‘perennially porous’. For Tracy, then, the phrase ‘essay’ tends to be thoughtlessly employed to categorise any cinematic text that does not immediately satisfy any pre-existing generic formula, and there is, in fact, little connection between the large array of cinematic works designated as ‘essayistic’.

Although I agree that the term ‘essay’ has too often been used by film critics without full consideration of its implications, I also believe that there is a coherent artistic philosophy that may be described as ‘essayistic’, and that this philosophy is distinctive enough to necessitate treating the audio-visual essay as a distinctive cinematic mode in its own right. I am hesitant, however, to describe the audio-visual essay as being a ‘genre’ in the traditional sense, as to do so would imply that there is a programmatic set of formal rules that a cinematic text must conform to in order to be recognised as an ‘essay’, such as voice-over narration, title cards, and the physical or aural presence of the filmmaker within the text. Any attempt to discuss the audio-visual essay along these lines inevitably fails to consider the wide range of devices and strategies that filmmakers have utilised throughout history to articulate essayistic discourse. In opposition to such a critical approach, I argue that the protean, hybrid quality of the audio-visual essay is precisely what makes it such a vital, enthralling branch of filmmaking in the contemporary landscape, as it actively challenges traditional representational assumptions, subverts pre-existing genre models, and deconstructs notions of photographic authenticity. In this sense, I concur with Corrigan’s argument that ‘[t]he difficulties in defining and explaining the essay are […] the reasons that the essay is so productively inventive’. It is not the intention of this article to discuss the audio-visual essay as a rigid taxonomic category with a strict checklist of formal features that must be satisfied. Instead, I posit that contextualising Marker’s work within the literary and cinematic tradition of the essay illuminates many of the challenging aspects of this filmmaker’s unorthodox body of work: its deliberate destabilisation of generic boundaries; its strategies of direct address; its formal self-reflexivity; and refusal to provide clear-cut conclusions to the theoretical issues it raises.

To better understand the essay as an artistic and intellectual mode, it is necessary to delve into the origins of the term in the writing of Michel de Montaigne. As M.A. Screech observes in his introduction to the 1993 translation of Montaigne’s Essays, Montaigne employs the French term ‘essai’, or ‘essayer’, to describe his artistic project. The term stems from the Latin term ‘to exagium’, meaning to ‘weigh’ or to ‘judge’ (1993, xii). Concerning his methodology, Montaigne tells the reader: ‘If my soul [âme] could only find a firm footing, I would not be assaying myself but resolving myself. But my soul is ever in apprenticeship and being tested’ (1993 [1580]: 908). The essay, according to Montaigne’s conception, is not a factual report of a truth that the essayist has already arrived at; instead, the essay is the direct expression of thought in the process of being formed, the act of an inquisitive and reflective enunciator putting forward ideas for further discussion and dissection by his audience. As Montaigne continues, ‘[t]here is no pleasure to me without communication: there is not so much as a sprightly thought comes into my mind that it does not grieve me to have produced alone, and that I have no one to tell it to’ (1993 [1580]: 457). For Montaigne, as for Marker, the act of essaying is incomplete unless there is a receptive second party who actively engages with the enunciator’s ideas and propositions.

Drawing on Montaigne’s conception of the literary essay, many theorists of the audio-visual essay have placed the process of communication at the core of their investigations into the potential for essayistic discourse to be carried over to the medium of cinema. Timothy Corrigan writes that the audio-visual essay is based on a ‘question-answer format initiated as a kind of Socratic dialogue’ (2011: 35). For Corrigan, the essayistic enunciator appears tentative in their pursuit of knowledge as they communicate to the viewer through direct address, and the attentive viewer must, in turn, interrogate the ideas being proposed. Paul Arthur connects the dialogical communication of the audio-visual essay directly to its impulse towards reflexivity. As Arthur writes, the cinematic essayist ruminates on a certain issue (or set of issues), while simultaneously reflecting inwards on the capacity of the medium to represent these issues. As such, the essayistic text ‘must proceed from one person’s set of assumptions, a particular framework of consciousness, rather than from a transparent, collective ‘We’’ (2003: 60). The cinematic essayist makes their presence known as they articulate a line of thought and assess different perspectives, while simultaneously communicating to the viewer that the topic is always open to further contemplation.

For the purpose of clarity and concision, I will briefly outline four characteristics of the essayistic impulse as it has been practised throughout the history of audio-visual art that I will take into account when considering its relationship to the possibilities of interactive digital technology. Firstly, it articulates a line of theoretical inquiry through sound and image. Secondly, in pursuing this line of reasoning, it reflects on the conditions of its own production, and hence reflects more broadly on the relationship between the image and the ‘real’. Thirdly, it is a protean form which may incorporate elements typically associated with the documentary, the avant-garde and narrative cinema. Finally, it communicates directly to the spectator through a process of dialogical exchange. I contend that the self-reflexivity and the impulse towards dialogic exchange of the audio-visual essay are fundamentally intertwined. The audio-visual essay, in my theorisation, is a fluid, self-reflexive form which problematises the viewer’s perception of the image as an authoritative document, instead calling attention to the mechanisms that produced the image, as well as the social, historical and political context in which the image is embedded. As such, cinematic essayists draw attention to the constructed nature of the cinematic text and, therefore, encourage the viewer to think critically about the validity of the artistic strategies they employ and the veracity of the observations they express.

Marker’s filmography offers a fascinating case study through which the aforementioned topics may be addressed, not only because he has produced a high number of essayistic works in a variety of different media (ranging from 16mm film, electronic video, digital and animation), but also because communicative negotiation has served as a fundamental structuring principle in Marker’s work since the very beginning of his career. For example, the verbal narration in Letter From Siberia (1958) directly asks rhetorical questions to the spectator, and calls upon them to consider how other filmmakers may interpret its images of the city in a different light to Marker. The multi-channel design of the installation piece Zapping Zone (1990) allows visitors to flit between the images on the monitors using the remote control, and therefore construct surprising contrasts and comparisons between the available pieces of footage.; Immemory is a work of hypermedia that organises a dense array of archival footage in a non-hierarchal structure that the user can browse in whatever order they desire. Rendered with a video game engine, Ouvroir is a virtual reality simulation that allows the spectator to perceptually explore a computer-generated ‘museum’ by operating an avatar. As the following sections will illustrate, Marker’s late work with new media utilises devices such as hyperlinks, navigable 3-dimensional virtual spaces and multi-option menus to advance his longstanding imperative towards spectatorial involvement. As his career developed, Marker continuously implemented new technologies into his craft, using them to simultaneously reflect upon the constantly transforming landscape of cinema and explore their potential for expanding the boundaries of his formal practice. Through a close examination of Marker’s diverse output, we may observe that the essayistic impulse need not be restricted to the format of the feature film, but may be carried over to a wide array of other audio-visual modes.

Amongst scholars of the audio-visual essay, Marker has consistently been hailed as an exemplary pioneer of the form. Indeed, one of the earliest articles that sought to discuss the essayistic potential of cinema was André Bazin’s review of Marker’s short travelogue Letter from Siberia. Bazin (2003 [1958]: 44) argued that, although it contained elements of non-fiction filmmaking, Letter from Siberia resembled:

[N]othing that we have ever seen before in films with a documentary basis’, and that it should, therefore, be approached ‘as an essay documented by film […] in the same sense as in literature; an historical and political essay, though. one written by a poet.

Marker’s practice is concerned not with treating images as objective snapshots of the pro-filmic world, but with foregrounding his own presence as an enunciator who consciously interprets, manipulates, and projects his personal preoccupations onto images. Throughout Letter from Siberia, the reflexive, multifaceted voice-over narration does not attempt to hide the fact that the filmmaker is observing the city through a lens of cultural difference, and therefore, his meditations may be vastly different from the views of those who have a closer relationship to the location. During one striking sequence, for example, images of workers and construction sites in the capital city of Yakutsk are shown, while the narrating voice articulates three potential avenues of interpretation: the first, a simple description of the names and geography of the buildings; the second, a revolutionary perspective detailing the need for the oppressed workers to rise up against the unjust working conditions on display; and the third, a right-wing voice expressing their desire to pass further legislation to crack down on union-lead industrial action to keep the city running efficiently. The narrator then reflects on the fact that, through the purposeful manipulation of the images which constitute the film, he could make the city appear as a ‘hell’ or a ‘paradise’, a utopian vision of urbanism of something more mundane. As Kristian Feigelson (2015: 84) observes, ‘the film’s commentary takes up the question of the distortion of reality by ‘objectivity’ and attempts to transcend the banality of images (of faces, forests or turbines in motion), in order to examine the filmic process more deeply’. Rather than offering a single, unified interpretation, the voice-over calls into question the possibility of an ‘objective’ account of his chosen location and raises questions regarding the many other potential approaches others may take to producing a cinematic account of the city. Marker’s short exemplifies David Montero’s (2012: 44) observation that the audio-visual essay tasks the spectator with negotiating ‘the multiplicity of meanings that images acquire in different temporal and discursive contexts (as well as their meaning in relation to those images that never were or failed to make it into a film)’. Instead of searching out a single, objective ‘truth’ about Siberia, then, Marker critiques the very notion that a cinematic text can offer an authoritative take on a topic, as the images that constitute it are always open to further perceptual reframing and individual contemplation.

Immemory: the audio-visual essay meets the computer database

During the later stages of his career, Marker developed a fascination with the potential of interactive digital technology to advance his imperative towards interpolating the viewer into a shared dialogical space. In Immemory and Ouvroir, Marker sets up a labyrinthine digital database of archival materials (photographs, videos, texts, digitally synthesised graphic designs), through which the spectator may search in an individualised, non-linear manner. Thus, Marker ensures that each spectator will have a quantitatively different experience of these works and that their experience will vary each time they engage with the project. Released on the cusp of the new millennium, Immemory is a monumental reflection on the Marker’s own life and artistic practice intertwined with a broader investigation into the socio-political history of the 20th century. Comparable in scope and ambition to Godard’s contemporaneous Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998), Immemory revisits symbols events, texts, images and themes that have haunted Marker since his origins as a filmmaker while expanding his montage practice by filtering them through the lens of an interactive CD-ROM. Aspects of Marker’s earlier works that are revisited in Immemory include: a fascination with Asian culture, with a particular focus on Peking (the photograph of the camels lining a path in the desert that is framed as the catalyst for Marker’s reflections on the city in Sunday in Peking is revisited here); a preoccupation with various leftist political movements that arose over the latter half of the twentieth century, such as the May ‘68 riots in France and the anti-Vietnam protests in America; the radicalism of Soviet montage cinema, and the ways in which its influence continues to shape contemporary political cinema (Aleksandr Medvedkin, the focus of Marker’s earlier audio-visual essay The Last Bolshevik (1992), takes on particular prominence); and the connection between cinematic form and the articulation of personal memory. Marker’s subjective viewpoint, therefore, pervades every aspect of Immemory, not as an aural or a physical presence but as an orchestrator of the audio-visual material that the viewer may navigate.

The viewer of Immemory is, then, sited in a dialogical relationship with Marker, whose presence as a mediating enunciative voice is inscribed into every element of the project. In his written introduction to Immemory, Marker (2020 [1997]) stresses that, though the project presents the viewer with ‘the guided tour of a memory’, he also aimed to provide the viewer with the freedom to pursue ‘haphazard navigation’. In his new media works, then, Marker provides the starting point for each individual’s essayistic journey, but does not determine its trajectory; each spectator must decide for themselves how they will traverse the dense collection of materials, what connections they will draw between them, and what conclusions they will derive from the encounter.

The composition of Immemory resembles a digitised photo album, with archival materials arranged across a series of interactive menu screens featuring hyperlinks that splinter off into various directions. Immemory is divided into seven different topographical ‘zones’, each of which is composed of a collection of audio-visual materials revolving broadly around a particular theme: ‘Cinema’, ‘Travel’, ‘Museum’, ‘Memory’, ‘Poetry’, ‘War’, and ‘Photography’, each of which may be accessed through the CD-ROM’s main menu (Figure 1). Each ‘zone’ is comprised of audio-visual material organised roughly according to a shared theme. Within a zone, the user can press an arrow on the right of the screen to move towards the next screen or click on the left of the screen to return to the previous page. Although this may seem to provide some semblance of a linear pathway through the database, Marker complicates this by embedding within almost every screen various interactive hotspots that the viewer may click on to access a different menu screen or to open various other materials. Marker refers to these elements as ‘bifurcations’, as they split the screen into a multitude of pathways upon which the viewer may embark. Marker actively encourages the viewer to explore these bifurcations, which lead to numerous forking pathways. Sometimes the bifurcation will lead the viewer to another pathway within the same zone, sometimes it will lead the viewer to a different zone, sometimes it will direct the viewer back to the page they were previously on, sometimes it will direct the viewer back to the main menu. The viewer can skip forward to the next screen by clicking the arrow on the right of each page, skip back by clicking the arrow on the left, return to the main menu by clicking the arrow at the top of the screen, and return to the beginning of each ‘zone’ by clicking an arrow at the bottom of the page.

The ‘zones’ of Immemory (1997).

The inscription of the author’s subjective voice, setting up a direct communication with the audience, and the selective incorporation of ‘found’ materials produced by other artists signify that Immemory is a truly essayistic work in the Montaignian tradition. Throughout the Essays, Montaigne highlights his own position as a critical reader as well as a writer. He describes his writing environment as an enormous library consisting of literary texts that influenced his development as an author, and he regularly ‘lifts’ passages (often at great length) from them to integrate them into his own essayistic reflections. At times, Montaigne accompanies the citation with his own critical commentary, and sometimes he allows the citation to speak for itself, letting the viewer determine its relationship to the surrounding textual fragments. Montaigne, therefore, emphasises that his essayistic reflections were not produced in isolation and they should not be received in isolation either, they were formed in response to artists who came before him, and they should, in turn, inspire the dialogical engagement of the spectator. Like Montaigne’s Essays, Immemory extracts a wide range of archival fragments from their original contexts for the contemplation of the spectator. Thus, the spectator is tasked with reacting to a text that never provides straightforward answers but perpetually opens up new issues of consideration through the dialectical tensions that arise from the re-contextualisation of audio-visual elements.

The rhizomatic, digressive structure of Immemory does not provide any suggested route through the archive, and it is near-impossible for the user to tell if they have viewed every piece of material available to access on the disk. This ensures that the path through the project will be qualitatively different for every user, and that every time the user revisits the project, they will experience it anew. ‘Don’t zap! Take your time’, is the advice Marker gives to the user in the introductory instructions screen, thus encouraging them to not be concerned with attempting to establish a straightforward path through the project, but to wander, reflect, and explore multiple diversions. In following Marker’s instructions, the viewer will actively establish their own unique path through the non-chronological assemblage of artefacts, and, therefore, become an engaged participant in the construction of essayistic meaning. My use of the term ‘rhizomatic’ is rooted in Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the ‘rhizome’, which they describe as a system in which ‘any point … can be connected to any other [point] and must be’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 7). As described elsewhere by Deleuze (1986, 120), who also referred to this concept as ‘any-space-whatevers’, the rhizome is:

[A]n amorphous set which has eliminated that which happened and acted in 9it … a collection of locations or positions which coexist independently of the temporal order which moves from one part to the other, independently of the connections and orientations which the vanished characters and situations gave to them.

The rhizome, therefore, describes a condition in which a space is constituted in such a way that an individual may move from one node to another without ever reaching a final destination. The open-ended, interactive infrastructure of Marker’s virtual museum may be understood through the lens of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of a rhizomatic space with ‘multiple points of entry’ divided into branches that stretch into infinity in various directions and create multiple points of convergence and divergence (Ibid). As the authorial figure, Marker sets up a series of responsive audio-visual elements that the spectator may actively navigate in order to conjure unexpected linkages and points of disjunction between the archival materials. It is through this relationship that the process of dialogical exchange takes place. Immemory, therefore, fosters an empathetic act of communication, one that not only allows the spectator to enter a closer relationship with Marker by dealing directly, materially, with the artefacts of the artist’s personal experiences, but also to achieve a more sophisticated conception of their relationship with their own past, and the way this relationship is shaped by material artefacts. As Marker explained in an interview conducted around the time of Immemory’s release, he was drawn to the digital database because its dispersed, non-linear structure seemed to capture the ‘aleatory and capricious character of memory’ (Alter, 2006: 148). Just as human memory constantly skips back and forth across moments in time, revisiting and repeating certain events according to a non-linear logic that makes sense only to the individual, Immemory does not package its collection of memory totems into a pre-established sequential order. As in the rhizome, or what Deleuze calls elsewhere the ‘anyspace-whatever’, the individual is constructed of ‘parts whose linking up and orientation are not determined in advance, and can be done in an infinite number of ways’ (Deleuze 1986, 109, 111–122). Immemory has no beginning and end points pre-determined by the author; it is up to the spectator to work their way through the interactive options and forge their own path. It is a space of ‘pure potential’, to borrow Deleuze’s terminology, a constantly shifting, open textual field that is never ‘complete’ and that offers a qualitatively different experience for every spectator (1986, 120).

The project, therefore, combines the dialogical structure of the essay form with interactive properties of return-channel digital media. As Rockley Miller (quoted in Jensen, 1999: 191) argues, the relationship between a user and a computer program may be described as being strongly interactive, even when the creator of the program is not literally present to provide a one-to-one response to their input. This is because the navigation of such a program relies upon:

[T]he active participation of the user in directing the flow of the computer or video program; a system which exchanges information with the viewer, processing the viewer’s input in order to generate the appropriate response within the context of the program.

The computer program remains inactive unless there is a user present who actively provides input values that activate a virtual response—the user’s actions play a vital role in determining the output of the computer program. This creates an interactive relationship wherein the functions performed by the digital program are dependent upon the commands given by the user, which, in turn, generates a tailored experience for the user and has an influence on the further commands they input into the machine.

Dominic M. McIver Lopes (2001) contrasts the interactive potential of computer media with the ‘unidirectional’ relationship between user and content fostered by broadcast television, the radio, and photochemical film. While those forms of media only allow for the viewer to be a receiver of pre-determined content produced by an artist, computer media is powered by a ‘return channel’ infrastructure’ that enables the spectator to exert direct control over their viewing experience by exerting commands over the screen content. Lopes, however, perceives of interactivity in digital media in terms of a continuum, ranging from ‘weakly interactive’ to ‘strongly interactive’ medial objects. Lopes uses the term ‘weakly interactive media’ to describe text which only allows the viewer a basic level of influence over screen content. For example, a Blu-Ray disc that contains an interactive menu feature is ‘interactive’ in the sense that it allows the user to select the point at which point in the narrative they start watching the cinematic text, it does not allow them to substantially alter the structure or shape of that text. In Lopes’ words, the Blu-Ray or DVD menu only allows the viewer to ‘control the sequence in which they access content’. Lopes contrasts this with ‘strongly interactive media’, in which ‘the structure itself is shaped in part by the interactor’s choices. Thus, strongly interactive artworks are those whose structural properties are partly determined by the interactor’s actions.’ The spectator may, therefore, reshape the ‘intrinsic or representational properties [the text] has, the apprehension of which are necessary for aesthetic engagement with it’ (Lopes, 2001: 68). In Immemory, Marker fragments and deconstructs recognisable elements of cinematic language – the shot, the audio clip, the intertitle – so that the spectator may recombine them into unique constellations. As such, Immemory may be described as ‘strongly interactive’, to borrow Lopes’ terminology, as the viewer has the power to construct their own individualised experience through the manipulation of malleable elements.

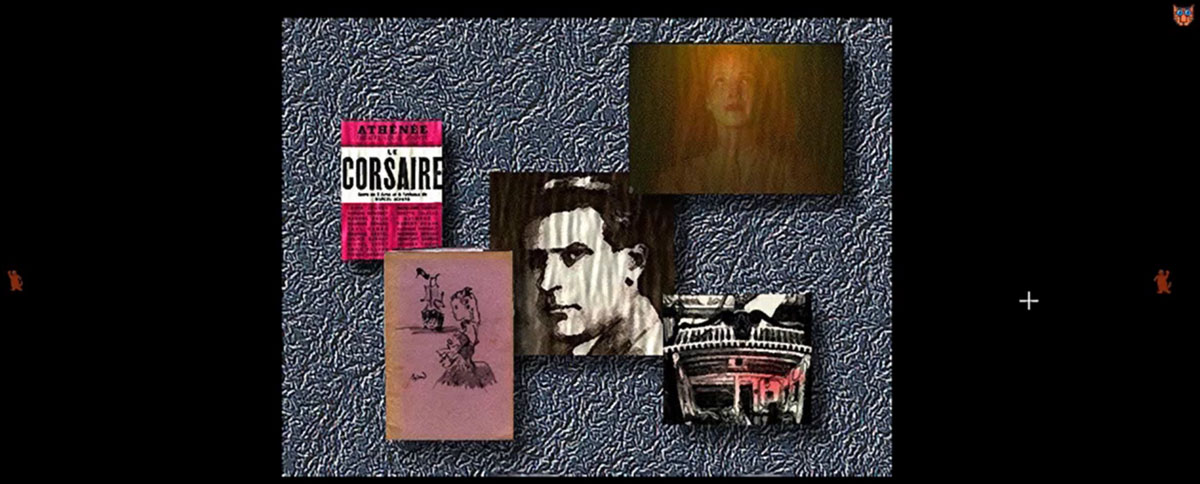

At one point in the project, Marker presents the spectator with a collection of clickable artefacts that the accompanying caption identifies as ‘Madeleines’ (Figure 2). The caption continues: ‘Thus one comes to call Madeleines all those objects, all those instants that can serve as triggers for the strange mechanism of Memory’. Marker has frequently claimed Proust as a major influence on his understanding of human memory, and here refers to the quotidian objects that activate subjective mnemonic associations throughout the author’s masterwork In Search of Lost Time. The most iconic example of such a mnemonic passage in Proust’s novel, of course, is the instance in which a madeleine pastry dipped in tea conjures memories of the narrator’s experiences in Combray with his Aunt Léonie. In Immemory, Marker re-imagines Proust’s literary ‘Madeleines’ as interactive audio-visual objects which, when clicked on, provide access to further digital hot spots. These totems are familiar objects: a postcard, a theatre program, a photograph of composer Vittorio Rieti, a book cover and a ‘do not disturb’ sign from a hotel. Clicking on one of these objects opens up a different forking pathway, which relates to some aspect of Marker’s personal history, either directly or obliquely. For example, clicking on the photograph of Vittorio Rieti brings the viewer to a new menu screen, from which they can access written biographical information about the composer, images of written correspondence, an audio snippet of one of his compositions, and an image of an oscilloscope reading. By clicking one of the hotspots, the viewer encounters Marker’s personal, tenuous relationship with Rieti: Rieti’s son Fabio would one day paint a collage of owls used by Marker in the series The Owl’s Legacy (1990). Therefore, the simple icon of the photograph expands outwards to a multitude of tangentially related archival materials, which the spectator may peruse at their leisure.

As Erika Balsom (2008) observes, Immemory ‘introduces an element of action into Proust’s more passive conception of involuntary memory, as it is precisely the trajectory decided upon by the viewer, possible only through interactive technology, that memory becomes actualized’. Rather than watching a pre-established stream of images that may trigger a personal memory, as the viewer would do in the classical paradigm of film spectatorship, the user of Immemory must actualise memory by making a series of active choices regarding which on-screen object to focus on, and which direction through the material to move in. In doing so, Marker encourages an ‘intensive mapping that forces the user into the creative role of determining his or her own trajectory through the work’ (Balsom, 2008). The user may carve a different path through the raw archival materials of Immemory each time they engage with the work and their perception of the relations between these materials is likely to be altered with each experience. As Nora Alter (2006: 121) observes:

There is no pre-established sequential logic. The route chosen by the viewer dramatically transforms him or her from the role of being a mere witness of Marker’s memory and lived history to that of a co-producer of histories and memories in the twentieth century.

Immemory does not present the user with a problem that can be ‘solved’ or a conflict that can be overcome. The project allows the user to reconfigure the materials of Marker’s personal archive into a theoretically infinite number of potential combinations according to their personal preferences, and each time the user does so they will forge new connections between the materials which, in turn, spur their own mnemonic associations. Marker, therefore, does not put across a single, fixed interpretation of history, but instead facilitates a pluralistic range of interpretations based on individual encounters with his digital mementoes. As Marker (1997) writes in his introduction to Immemory, his ultimate ambition with the project was to create a work that would enable the viewer to reflect on the processes through which their own memories are formulated:

My fondest wish is that there might be enough familiar codes here (the travel picture, the family album, the totem animal) that the reader-visitor could imperceptibly come to replace my images with his, my memories with his, and that my Immemory should serve as a springboard for his own pilgrimage.

The externalisation of Marker’s memory in the form of a freely navigable database, then, was intended to more accurately resemble the way that actual human memory functions than would be possible to achieve through the form of a feature film. As Marker makes clear, the participative, non-linear nature of the project is designed to make the mechanisms of memory more perceptible to the user, so that their own, personal act of remembrance may be triggered. In the process of essayistic communication, what is most important is not that the separate parties synthesise their individual perspectives into a single, unified conclusion (an outcome that, as I have illustrated, the audio-visual essay inherently resists), but that the conditions for an exchange of communication between one party and another are established. Marker’s interactive interface invites the spectator to enter into a personalised, subjective relationship with historical artefacts, rather than to view these archival documents as transparent windows into the past. Because there is no pre-established line of response, and there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to interact with the collected materials, the project enables the viewer to develop an individual conception of the past and their place within it; the negotiation of meaning in Immemory occurs through the spectator’s unique engagement with the text, and this process will vary from spectator to spectator.

Ouvroir: empowering the gaze of the spectator within virtual space

With Ouvroir, a virtual museum constructed within the web-based role-playing game Second Life, Marker carried over his fascination with the archival possibilities of digital technology into the realm of three-dimensional simulation. Second Life is a never-ending, three-dimensional platform game without hierarchal levels, manufactured conflicts, or clear objectives, instead setting up a virtual environment in which users may converse with other players, build architectural spaces, upload multimedia objects from their computer hard drive, and pursue their own self-defined goals. When a user constructs a new architectural space within the game, it becomes available for other users to engage with. Second Life, then, offers the user a great number of possible spectatorial experiences, as the viewer may explore and interact with a series of constantly expanding and evolving computer-generated environments with no pre-set guiding path. The never-ending, participative nature of Second Life proved attractive to Marker, who recognised its potential to aid him in reimagining the museal possibilities of the virtual database and granting the viewer increased agency over their spectatorial experience. Ouvroir arranges a range of archival audio-visual materials around the space of a computer-generated archipelago, which the user may navigate through the avatar of the anthropomorphic ginger cat Monsieur Guillaume – a CGI creation based on an illustrated character who appears in different iterations throughout several of Marker’s other late-period projects. The archipelago is divided into several different sections, each of which is housed in a different enclosure. These spaces are arranged across several levels, connected through bridges, alleys and corridors. Although the structure vaguely resembles that of a real-world material museum, several aspects of its design defy the laws of physics: bridges float above the water with no support, a large red orb is suspended in the air, and small objects drift across the environment in all directions in an unpredictable pattern (Figure 3).

Within each of these simulated spaces is contained a collection of digitised archival materials, each one relating to some aspect of Marker’s life and/or work. As in Immemory, these items are all connected to Marker’s life and works in some way, ranging from digitally remediated images and clips from the filmmaker’s previous features, Marker’s still photography, totems from countries and historical eras that have featured prominently in Marker’s earlier artworks, or images from the features of Marker’s claimed artistic inspirations (including Kurosawa, Tarkovsky, and Medvedkin – three filmmakers who have served as subjects for short essays by Marker in the past). In one of the central galleries of Ouvroir, multiple images from Marker’s book of portrait photography Staring Back (2007) are dispersed across the perimeter of the room, as if hanging in an art exhibit. In the middle of the space sits a table, across which eight objects are displayed. The objects are miniature digital reproductions of eight books, which resemble miniature, digitised versions of travel books written by Marker during his early years as a photojournalist (Figure 4).

Ouvroir grants the user more possibilities for perceptually exploring the digital database than in Immemory by extending the ambulatory gaze into multi-directional, simulated space. While Immemory allows the user to perceptually engage with screen content by using the cursor to select options presented to them in a series of two-dimensional menu screens, Ouvroir allows the viewer to feel as though they are physically traversing an environment along the x-, y- and z-axis. In addition to being able to track forward, back and side to side through the computerised museum, the spectator may use the mouse or the arrow keys to direct the focalising perspective of their avatar across a 360° plane. Immersed in the screen space of Ouvroir, the spectator is free to zoom into different parts of the museal objects, to view them from different angles, or even to position their perspective so that only a fraction of the object is visible on their monitor. As the spectator is able to intuitively control the direction, speed and perspective of the avatar, they have a greater level of freedom in determining their perceptual experience of the archival materials.

Like Immemory, Ouvroir is not only constructed in such a way that permits meandering on the user’s part, but the construction of the project is intended to destabilise the viewer. Marker does not provide the spectator with a stable, linear path through the dense collection of archival materials. To do so would imply that there is a fixed, correct way of consuming the archival totems, and therefore set up a uniform spectatorial position that would be identical for every user. Such a design would be antithetical to the very ideological nature of the project. Any attempt that the viewer may make at traversing the entire space of the archipelago in a straightforward line of motion is bound to end in frustration. The museal spaces are arranged in no clear order, and the maze-like passages that connect them branch out into multiple forking paths, some of which lead the spectator to a dead end, while others lead the spectator to a path they have already crossed. At times, the impression of solid, traversable architecture breaks down entirely, such as in one ‘underground’ compartment, which exists as a shadowy, abstracted area in which an assemblage of still and moving images (some with visible borders, some without) drift across the contours of the screen in a randomised sequence. This environment does not align with any traditional model of realistic architectural space, and the unpredictable movement of the images across the x-, y- and z-axis means that the user cannot establish a stable vantage point that would allow them to clearly see all of the artworks (Figure 5). This interplay between recognisable elements of architectural space and spatiotemporal distortion results in what Jihoon Kim (2020: 99) describes as a ‘spatial instability’ that is suspended between ‘the uncanny coexistence of boundedness and boundlessness’. The difficulty of establishing a stable trajectory through this virtual environment forces the user to engage in substantial intellectual labour; they must make a concerted effort to map their way through the often-destabilising blocks of space, to view the vast reservoir of audio-visual materials in a non-linear and individualised way, and, in doing so, to traverse the contours of their own memory.

This article has discussed Marker’s essayistic filmmaking as a dialogical process that interpolates the spectator into a process of communicative exchange. As I have argued, Marker employs a range of epistemological strategies to draw the viewer into a shared communicative space and, therefore, to develop an active, critical engagement with the text. As he incorporated digital technologies into his craft, Marker wedded this dialogical impulse with an interest in the archival potential of the computerised database, producing a series of works that recalibrate the bond between filmmaker and viewer by allowing the spectator to materially engage with the interactive interface. By setting up interactive virtual spaces in which a multitude of digitised archival objects may be navigated in a non-linear and customisable order, Marker reflexively explores the interactive nature of the computational interface and the opportunities it offers to revitalise the communicative potential of the audio-visual essay.

Immemory and Ouvroir are both projects that have no definitive beginning or ending points. The spectator may select their own starting position, embark on their essayistic encounter, and then finish the experience whenever they choose. Even though the essayistic feature film may employ strategies of direct address, alter the chronology of events, and incorporate techniques of distanciation to provoke active and critical spectatorship, the open-endedness and the interactivity of digital media enables the viewer to determine the conditions of their perceptual journey with a greater degree of freedom. The empowerment of the spectator’s gaze in Marker’s late digital projects does not, however, mean that the authorial presence of the filmmaker is concealed; like Marker’s earlier essayistic works, Immemory and Ouvroir foreground the presence of Marker as a figure who provides the tools and establishes the topics of philosophical enquiry that form the building blocks of the spectator’s intellectual navigation. It is through the tension between the agency afforded to the viewer and the boundaries that delimit the user’s choices that the dialogical communication between filmmaker and spectator takes place. Asked in an interview about his overarching filmmaking ambitions, Marker remarked that he ‘tr[ies] to give the power of speech to people who don’t have it, and, when it’s possible, to help them find their own means of expression’ (Douhaire, Rivoire and de Baecque, 2003: 39). By embracing new media, Marker developed a range of effective devices for breaking down the hierarchy between author and viewer. In Immemory and Ouvroir, essayistic meaning is produced through the exchange between Marker’s arrangement of digitised archival footage, and the linkages forced by the viewer as they actively work through these objects. In the process, essayistic meaning is actively negotiated in the exchange between the organisation of digitised archival fragments collected by Marker and the linkages forged by the viewer as they actively navigate these elements.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Alter, N 2006 Chris Marker (Contemporary Film Directors). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Arthur, P 2003 Essay Questions: From Alain Resnais to Michael Moore. Film Comment, 39(1): 58–62.

Bazin, A 2003 [1958] Bazin on Marker. Kehr, D (trans.) Film Comment, 39 (4): 44–45.

Bensmaïa, R 1987 The Barthes Effect: The Essay as Reflective Text. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Corrigan, T 2011 The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deleuze, G 1986 Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Tomlinson, H. and Habberjam, H (trans.) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G and Guattari, F 1987 A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Massumi, B (trans.) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Douhaire, D and Rivoire, A 2003 ‘Marker Direct: An Interview with Chris Marker’. Film Comment, 39(3): 38–41.

Feigelson, K 2015 Chris Marker: Interactive Screen and Memory. In: Post-1990 Documentary: Reconfiguring Independence. by Deprez, C. and Pernin, J (ed.), Zelman, J. (trans.) Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp.82–97. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748694136.003.0006

Jensen, J.F 1999 Interactivity: Tracking A New Concept in Media and Communication Studies. Nordicom Review, 12:1: 185–204.

Kim, J 2020 The archive with a virtual museum: The (im)possibility of the digital archive in Chris Marker’s Ouvroir. Memory Studies, 13(1): 90–106. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1750698018766386

Lopes, D M M 2001 The Ontology of Interactive Art. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 35(4): 65–81. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/3333787

Marker, C 2007 Staring Back. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marker, C 2020 [1997] Immemory by Chris Marker, 13 August 2020. Available: https://chrismarker.org/chris-marker/immemory-by-chris-marker/. [Last accessed 20 December 2021].

Montaigne, M 1993 [1580] The Complete Essays. Screech, M A (ed. and trans.) New York: Penguin.

Montero, D 2012 Thinking Images: The Essay Film as a Dialogic Form in European Cinema. Berlin: Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften.

Rascaroli, L 2009 The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film. London: Wallflower Press.

Rodowick, D N 2007 The Virtual Life of Film Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4159/9780674042834

Screech, M A 1993 Introduction. In: Montaigne, M 2003 [1580] The Complete Essays. Screech, M A (ed. and trans.) New York: Penguin: i–xxxiv.

Tracy, A 2013 The Essay Film. Sight and Sound. Available: https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sightsound-magazine/features/deep-focus/essay-film [Accessed 12/08/2021]

Filmography

Histoire(s) du cinéma. 1998. [Film] Jean-Luc Godard. France: Canal+, Centre National de la Cinématographie, France 3, Gaumont, La Sept, Télévision Suisse Romande, Vega Films.

Immemory. 1997. [CD-ROM] Chris Marker. France: Direction des Editions du Centre Pompidou.

Le Tombeau d’Alexandre [The Last Bolshevik]. 1992. [Film] Chris Marker. France: Les Films de l’Astrophore and CNC.

Lettre de Sibérie [Letter from Siberia]. 1958. [Film] Chris Marker. France: Pavox Films and Argos Films.

L’Héritage de la chouette [The Owl’s Legacy]. 1990. [TV] Chris Marker. France: Icarus Films.

Ouvroir. 2012. [Online Resource] Chris Marker. United States: Second Life. Available: https://secondlife.com/destination/ouvroir-chris-marker. [Accessed December 5th, 2021].

Zapping Zone. 1990. [Installation] Chris Marker. France: Centre Pompidou.