Introduction

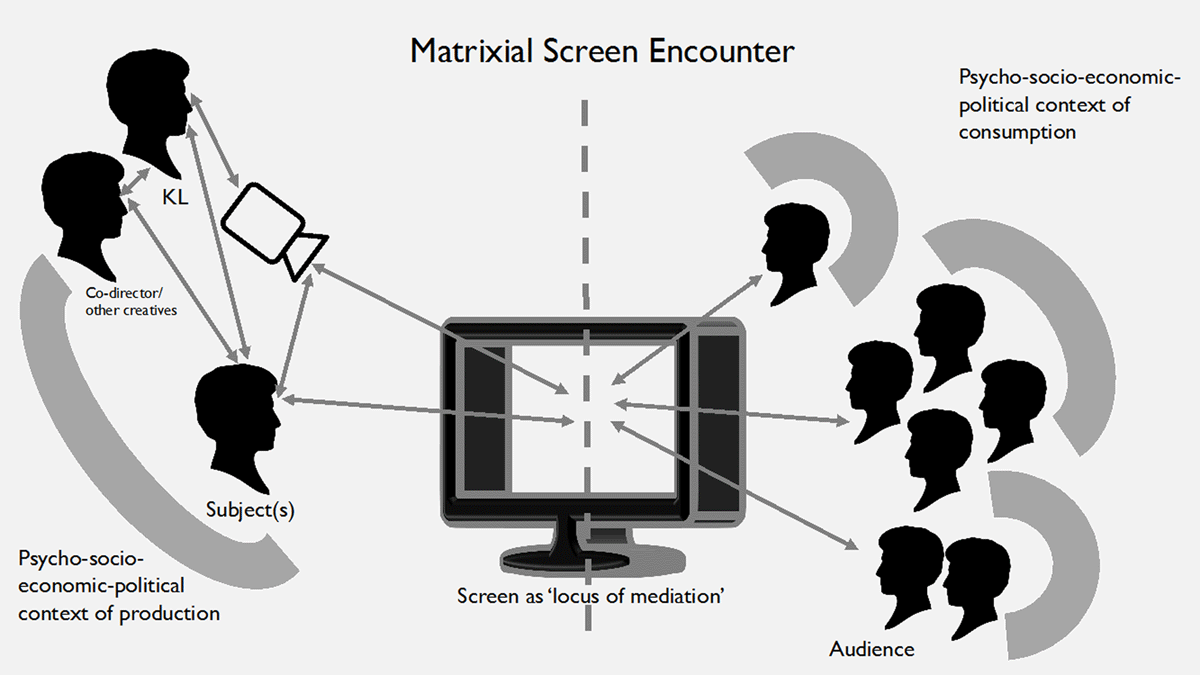

This article considers how we can theorise the documentary practice of Kim Longinotto. Her work is often categorised within the observational mode of documentary, which is associated with neutrality where the camera is like ‘a fly on the wall’. When teaching Longinotto in the classroom, the dual connotation of neutrality and a singular perspective embedded in this metaphor are an inadequate reflection of her highly collaborative approach to documentary filmmaking. As a director, Longinotto is closely entwined with the goals and aspirations of her subjects, who are almost always women rebelling against systems of patriarchal oppression. This article explores how the emphasis on intersubjectivity and collective action in Bracha Ettinger’s notion of the matrixial provides a more appropriate model for theorising Longinotto. I argue that the matrixial screen encounter allows us to re-think the individualistic framing of the auteur, as it includes all creatives and subjects/actors involved in the production of any filmic text. It also allows us to consider the inter-subjective gazes or layers of power within any film text, as well as the psycho-socio-economic-political contexts of production and consumption. It can therefore be applied to any creative work where multiple creatives, subjects, or actors contribute to the text.

Kim Longinotto is a white, female English documentary filmmaker who has been directing documentaries since 1976. Her output has been prolific, producing more than 20 films with a distinctly international scope, made in England, Northern Ireland/the North of Ireland, the USA, Italy, Iran, Egypt, Kenya, Cameroon, South Africa, India and Japan. Her first film Pride of Place (1976) sets the tone and subject matter of her subsequent filmmaking practice. It centres on Longinotto’s school, a strict boarding school for girls that inculcated its pupils with a rigid sense of British class structure. The school thought its role was to prepare girls to behave appropriately as middle-class operands within this class system. As a child from a working-class background, Longinotto felt like an outsider. She described how she was labelled a ‘class traitor’ by her former Headmistress after a screening of the film (Cochrane, 2010, n.p.). This sets the context for her later work, which centres on the experiences of women across multiple countries and cultures whom Longinotto (cited in Smaill, 2007: 178) describes as ‘outsiders’ who are rebelling against systems of oppressive patriarchal power. The films often show women who work within and outside such systems in order to challenge, subvert, change or escape them. Sisters In Law (2005), for example, centres on female lawyers in Cameroon who are working to effect change for women who are oppressed by patriarchal legal systems. The film ends with the lawyers’ first successful conviction for spousal abuse, a trial initiated by women from the Muslim community. Longinotto’s ‘Japan’ series, as it is known, centres on women who challenge normative gender boundaries such as the Gaea Girls (2002) female wrestlers or the Shinjuku Boys (1998), a group of transgender men who work in a nightclub in Tokyo. She is perhaps best known for her 2002 film The Day I Will Never Forget, which centres on the stories of women and girls in Kenya who have experienced female genital mutilation. On the whole, Longinotto’s extraordinary body of work expresses complex themes around female bodies and how they operate within, and are subjected to, patriarchal bodies of power.

Despite this extensive filmography and her essential contribution to documentary practice, Longinotto’s work is under-taught in documentary syllabuses. To counter this, I include Longinotto in my undergraduate documentary modules in order to highlight her central contribution to the field; however, I struggled to find a theoretical framework that adequately reflected Longinotto’s distinctly feminist and collaborative style. Documentary teaching tends to rely on theorists such as Nichols (2001), Bruzzi (2006) and Renov (2012), with emphasis on Nichols’s (2001) modes of documentary. Critiqued by Bruzzi (2006) as overly simplistic, these modes categorise documentaries in relation to their aesthetic style and purpose: expository, poetic, performative, reflexive, participatory and observational. Longinotto’s style is often categorised within the observational mode, which Nichols (2001: 34) describes as one where events are ‘observed by an unobtrusive camera’. The term therefore has connotations of impartiality, where a supposedly neutral camera acts like a ‘fly on the wall,’ dispassionately observing events without actively shaping them.

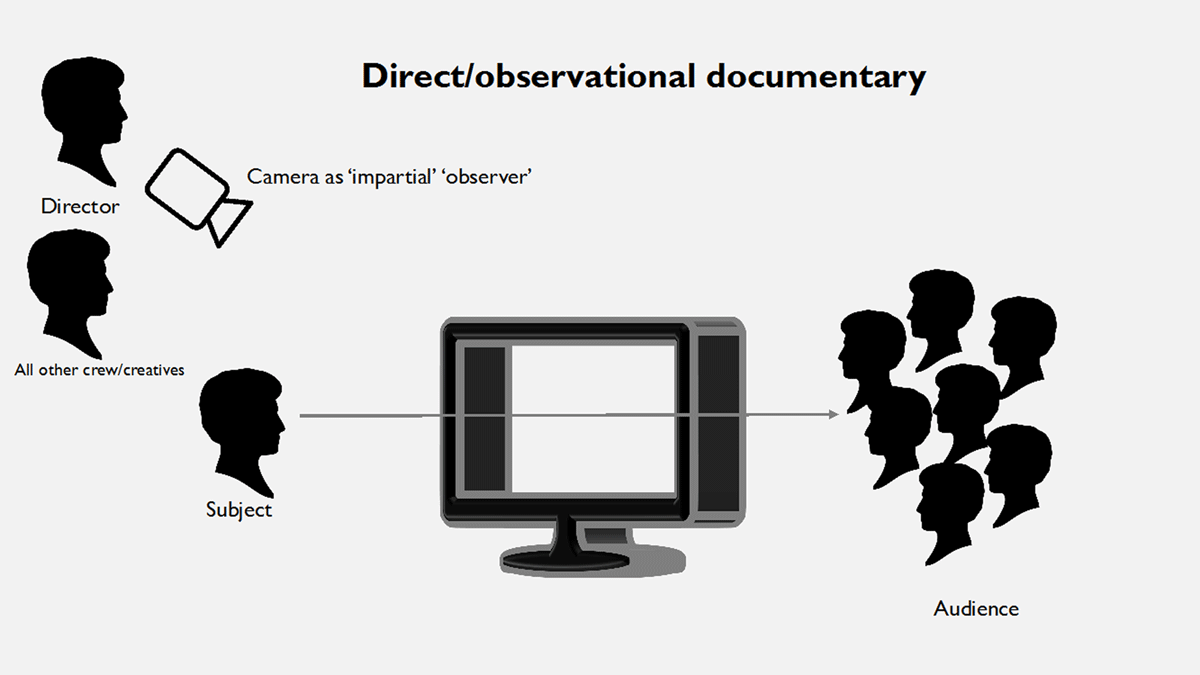

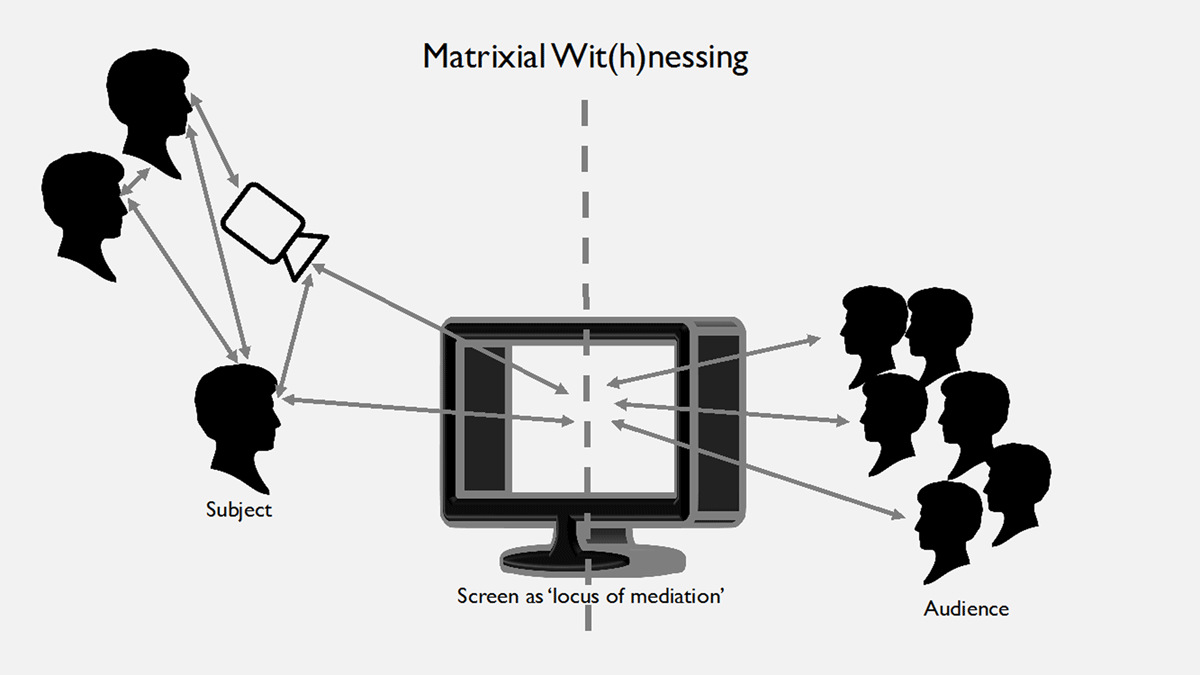

This observational style of documentary filmmaking arose in the 1950s and 1960s as cinéma vérité in France, led by Jean and Edgar Morin, and as Direct Cinema in the US, led by Robert Drew. The proponents of direct cinema held the view that they could ‘act in such a way as not to affect’ the subjects of their films (Richard Leacock, cited in Cousins and Macdonald 1996: 256). This assumes a model of direct interaction between subject and audience with minimal layers of mediation between the two:

Whilst Longinotto’s work is often pigeon-holed within these categories, she rejects the notion of the camera as impartial observer:

I hate the expression “fly on the wall”, which people still use. It seems such an old-fashioned expression, because for me that makes you feel like the filmmaker is like a kind of non-feeling, non-present person that’s just observing in a cold way – there’s no other way to interpret that. And I think a lot of early observational films, people took that very much to heart and so if people spoke to them they would get embarrassed, they wouldn’t meet people’s eyes (…) but I actually really like it if people acknowledge me so there’s scenes you’ll see in all the films like in ‘Divorce’ at one point the woman comes in she sort of makes us film her, then she whispers into the camera (…) and I love that because then it’s like a play within a play and the audience is let in because they’re speaking to me but they’re speaking to you. (…) So, in a way sometimes I think we’re a little bit, we can be (…), people can be a little bit patronising and assume that somehow people don’t know they’re being filmed or don’t know what it entails. (…) So, you can see in scenes people going in and out of being aware of the camera. It’s really good if people watch [documentary] films like they watch fiction. If you watch it for the layers and all the shifts and all the different meanings in it (Longinotto, interview with BFI, 2013).

Murray (2018: 92–93) recognises the formal qualities that Longinotto’s documentaries share with fiction films. She argues that her highly narrativized approach overlaps with fictive filmmaking techniques:

Observational simplicity and direct emotion arise out of collaborative craft incorporating fictional conventions. (…) Longinotto was always driven by storytelling (…). Examined in the light of this poetic sensibility, Longinotto’s form of observational documentary draws quite overtly on established melodramatic modes of cinema. Her authorial voice (…) is a blend of the generic structures used, both of documentary and of fictional melodrama.

When teaching Longinotto, Nichols’s observational mode therefore seemed an inadequate way of theorising her documentary practice. The observational or vérité label remains useful for considering her aesthetic style; as Cousins and Macdonald (2006: 251) state, ‘these days cinéma vérité is a vague blanket term which [is] used to describe the look of a feature or documentary films – grainy, hand-held camera, real locations – rather than any genuine aspirations the filmmakers may have’; however, aesthetics are not the sum total of observational documentary. Ulfsdotter and Backman Rogers (2018b: 1) go further to suggest that ‘many scholars now agree that the conventional labels – in the form of, by way of example, cinéma vérité or observational cinema – are at best inadequate, and thus call for reinvention’. I therefore felt the need to find a theoretical model that rejects the notion of the camera as impartial observer.

Similarly, I was interested in notions of the gaze in the Mulverian sense and wanted to theorise Longinotto’s gaze in a way that reflects her entanglement with the aims and aspirations of her subjects. Despite critique (Snow, 1989, Coorlawala, 1996) the notion of the male gaze is well established in film studies and the notion of the female gaze is increasingly being considered in fiction film. Malone (2018), for example, offers an outline of the gaze of a range of female fiction filmmakers, but doesn’t offer a theoretical model for conceptualising it. Little attention has been paid to theorising the gaze in documentary studies, particularly in relation to female documentary filmmakers. As Smaill (2018: xiii) states, ‘the relationship between feminist approaches and documentary film has never been adequately addressed in film studies. Despite the critiques of essentialism, there has often been counter attempts to define the female gaze’. Waldman and Walker’s (1999: 3) pioneering text offers one of the first collections of scholarship that specifically addresses documentary filmmaking as feminist practice where they acknowledge ‘feminism and documentary as one unbounded and mostly uncharted universe’. More recently, Ulfsdotter and Backman Rogers (2018a) offer one of the first attempts to consider female agency and authorship in documentary practice. Like Smaill, they acknowledge that attempts to theorise the female gaze inevitably raise the thorny issue of essentialism. Lisa French counters these concerns by arguing that, rather than reinforcing gender essentialism, the intent in theorising the female gaze is to acknowledge that there are commonalities in how women experience gender across multiple cultures:

Difference caused by experiencing gender (…) alludes to something that connects women. It implies a sensibility to female experience (…). While the argument that subjectivity relates to the sexed body could be critiqued as essentialist, it is not the argument that women have the same experiences in their lives or their bodies, but rather that gender causes an inflection which might be described as an awareness of ‘Otherness’ or difference, and that women share this and recognise it as a factor of the experience of patriarchal cultures (French, 2018: 10–11).

Longinotto’s body of work is chiefly concerned with the female experience as ‘other’ and how it is positioned as such within systems of patriarchal power across multiple cultures. This article sits within this body of literature on feminism and documentary and aims to contribute to ‘the urgent need for a scholarly study of the specific relationship between female authorship and the documentary image’ (Ulfsdotter and Backman Rogers, 2018b: 1). My intention is to find a theoretical framework that encompasses notions of subjectivity/objectivity and recognizes that the gaze is not driven by a single auteur but is shared between co-directors and subjects. Taken alone, neither the observational mode nor the concept of the gendered gaze is sufficient to reflect Longinotto’s inter-connected, collaborative approach, but I argue here that Ettinger’s notion of the matrixial offers a provocative solution to this theoretical conundrum.

The Matrixial Screen Encounter

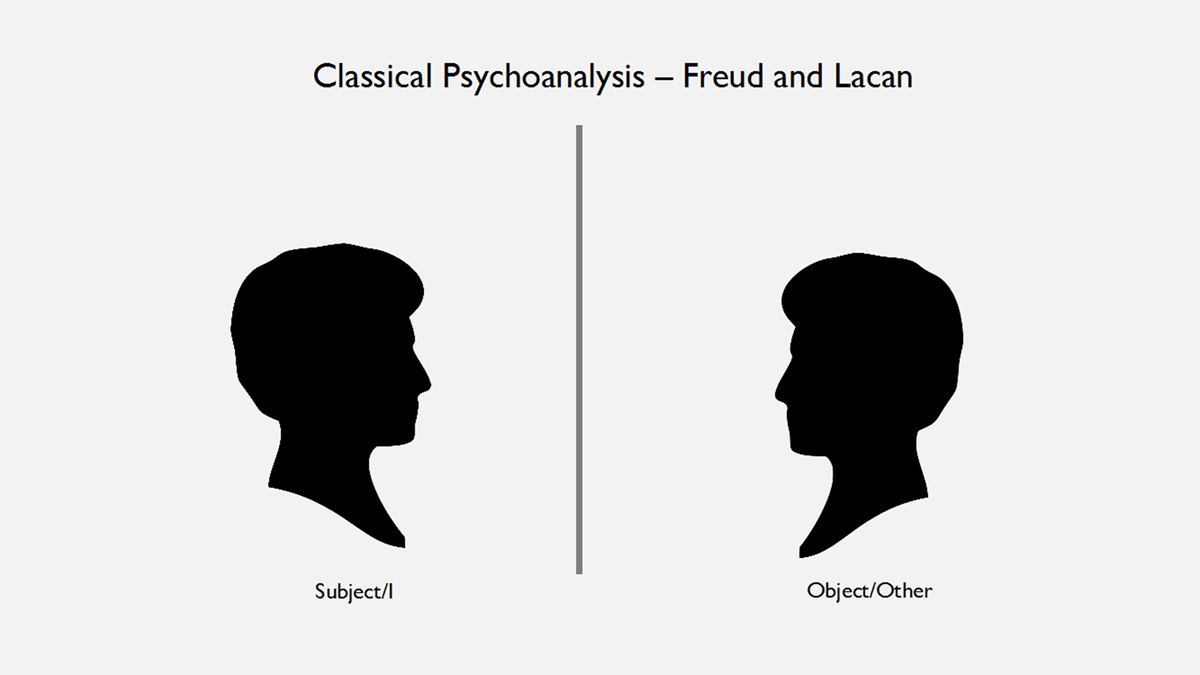

In searching for models that might help conceptualise Longinotto’s collaborative style, I came across the work of psychoanalyst and painter Bracha Ettinger and her notion of the matrixial. In documentary terms, ‘psychoanalytically informed approaches to film have been confined, almost exclusively, to fiction film’ and despite ‘Renov and Nichols’ insist(ence) on the applicability of psychoanalysis for the study of documentary film ((…) neither really models the project)’ (Walker and Waldman, 1999: 24). Applying Ettinger’s notion of the matrixial to documentary therefore seemed like an opportunity that has been missed by documentary scholars. Based loosely on the concept of the ‘womb’ as a counter to the phallus, Ettinger proposes that the pre-natal connection of the foetus to the mother creates a sub and pre-conscious disruption of distinct separation between the ‘I’ and ‘Other’, or ‘I’ and ‘(m)other’, as Ettinger describes it. She uses the term matrix, or matrixial, as a conceptual reference to the womb and an expression of this sense of inter-connectedness. She proposes that this feeling isn’t confined solely to the prenatal stage but continues throughout the lifespan. These ideas are rooted in phenomenological psychoanalysis, building upon the work of Merleau-Ponty and Deleuze while challenging the phallocentric theories of Freud and Lacan. The matrixial is based on the premise of inter-subjectivity, or the reduction of clear distinctions or borders between ‘I’ and ‘Other’. In Lacanian or Freudian terms, these boundaries are positioned as a series of rifts, splits and cleavages, where the Subject/I and Object/Other are dichotomous opposites that are distinctly separate:

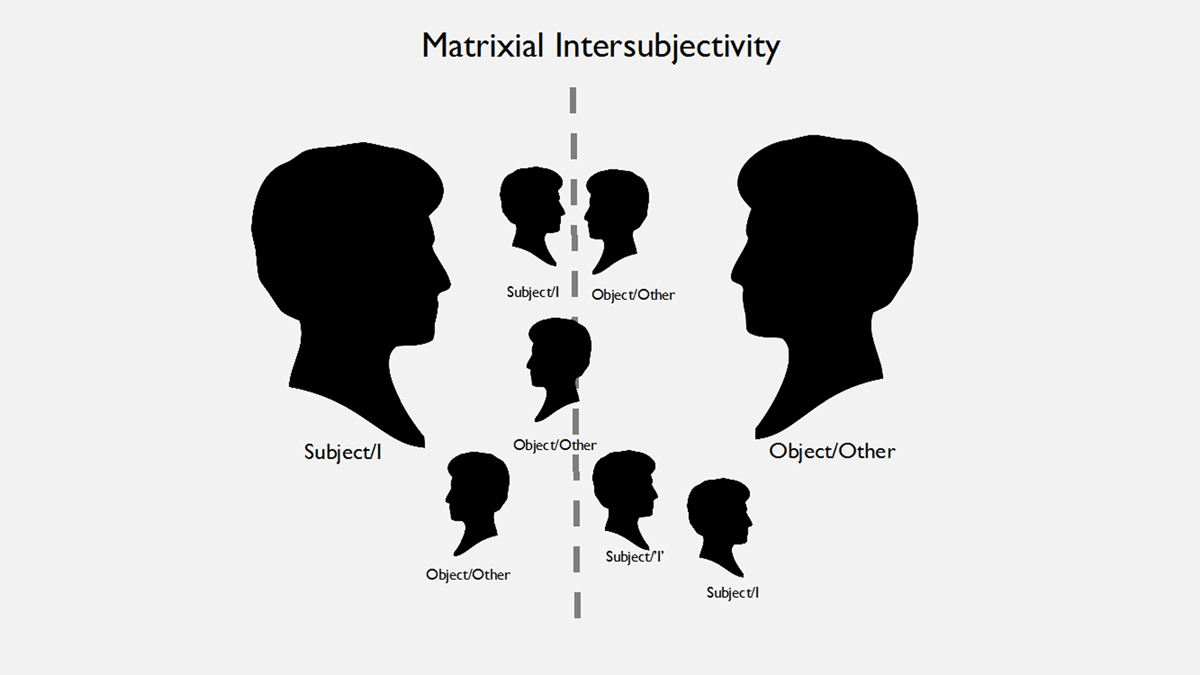

In contrast, Ettinger (2001: 103) argues that there is no clear separation between subject and object. The matrixial proposes inter-subjectivity between subject and object, I and Other that is framed as an encounter rather than a decisive ‘split’:

The notion of the non-separate I/(m)Other echoes Butler’s (2005: 19) ‘theory of subject formation that acknowledges the limits of self-knowledge,’ which posits that the formation of one’s sense of self in relation to the ‘other’ is an on-going, relational, inter-dependent process:

The opacity of the subject may be a consequence of its being conceived as a relational being, one whose early and primary relations are not always available to conscious knowledge. Moments of unknowingness about oneself tend to emerge in the context of relations to others, suggesting that these relations call upon primary forms of relationality that are not always available to explicit and reflective thematization. If we are formed in the context of relations that become partially irrecoverable to us, then that opacity seems built into our formation and follows from our status as beings who are formed in relations of dependency.

Similarly, in the matrixial, the subject and object are not distinctly separate, but instead are inter-connected in what Ettinger (2001: 104) terms ‘borderlinking’, which emerges ‘via the subject’s early contact with a woman’. She further describes borderlinking as a ‘(connection, “rapport”) (…) (which) is an operation of joining-in-separating with/from the other’ (ibid.). In other words, our early connection to a female body in the womb creates a sense connection to the (m)other which continues throughout the lifespan. Ettinger applies this to her practice as a painter where she experiences a similar sense of connection with the artwork and audience. She states that it was her:

Immersion in painting (…) (that) led (her) to apprehend a matrixial borderspace beyond the phallus in the field of experience and representation (…). Via the subject’s early contact with a woman (…), there emerges a swerve and borderlinking (Ettinger 2001: 104).

Expanding this concept to the creative process, the ‘matrixial gaze and screen enable(s) us to perceive and theorise differing links connecting artist, viewer and artwork’ (Ettinger 2001: 107) and that this ‘ultimately posit(s) this matrixial sphere as an aesthetic field and offer(s) a model of borderlinking useful for discussing a range of artistic phenomena’ (ibid., 109).

Borderlinking – which recognizes the interconnectedness of artist, subject and viewer – seems a particularly apt way of theorising the documentary practice of Longinotto. Longinotto’s work is matrixial in that she, her co-directors, crew, and subjects work together as an interconnected web, or matrix. She states that ‘the kind of film I like to make are where I feel like I’m making them with people (…) and we’re like two teams working together on one team’ (Longinotto, interview with BFI, 2013). The matrixial allows us to recognise and consider the inter-connected web of creatives and subjects that contribute to any film or documentary, negating the assumption that authorship or auteur status must rely on singular creative agency.

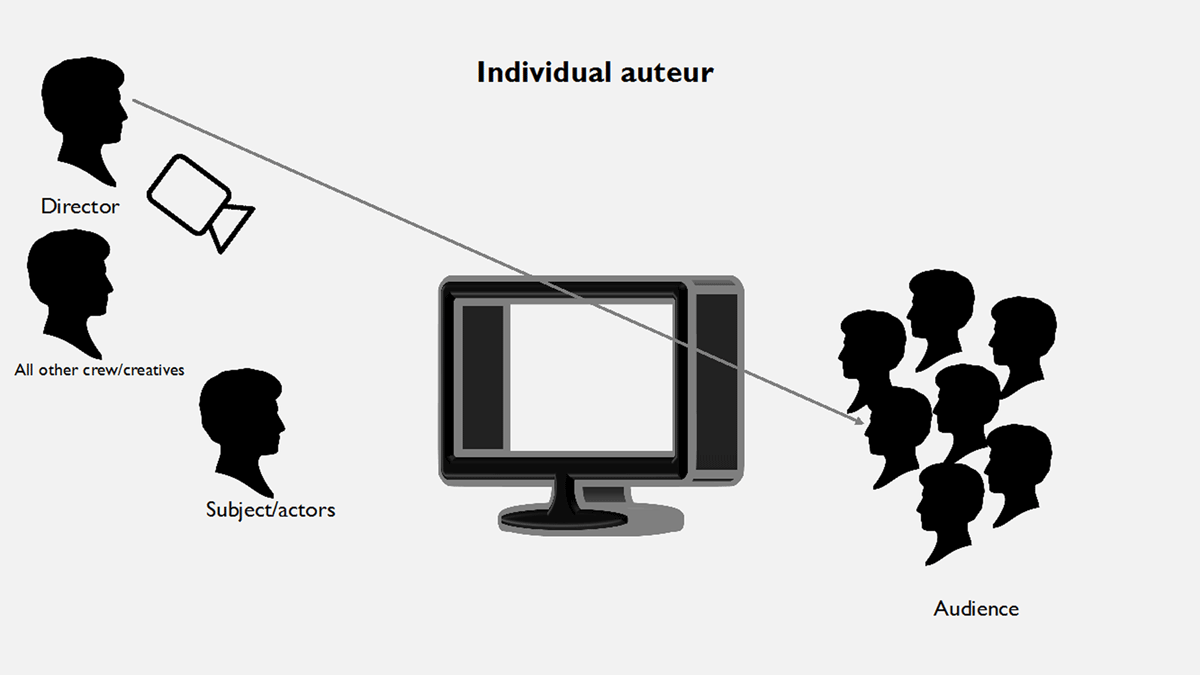

Framing the encounter between subject and object as a form of borderlinking reduces the paternalistic power of the single author or auteur. The matrixial model cannot be reduced to the unitary, singular, often paternalistic notion of the ‘gaze’ of the director, which has been implicitly or explicitly understood to pass directly to the audience with minimal meditation:

This aligns with Longinotto’s insistence on crediting her collaborators as co-directors – for example, Ziba Mir-Hosseini, with whom she worked closely on Divorce Iranian Style and Florence Ayisi, with whom she worked on Sisters in Law. Whilst Longinotto makes her own artistic approach clear – she writes extensively about the making of her 2013 film Salma and her strong authorial role in structuring the narrative with an editor – her tendency to acknowledge co-directors fits with the matrixial notion of inter-subjectivity. This better reflects:

Longinotto’s collaborative practice is a particular kind of citation or series of statements that positions her auteur status in the field of documentary as a non-normative one. These projects consistently bear the marks of a strong consultative process that seeks input from not only co-directors, but also women already working in the environments depicted. This expression of collaboration and its attendant reciprocity entails a translation of meaning between authoring subjects, frequently in the interests of a mutual social agenda (Smaill, 2015: 91).

In outlining how the Divorce Iranian Style came about, Longinotto’s co-director Mir-Hosseini (1999: 17) confirms that:

The idea of making a film about the working of Shari’a law in a Tehran family court was born in early 1996 when a friend introduced me to Kim Longinotto, the documentary filmmaker. I had seen and liked Kim’s film, “Hidden Faces” (1991), on women in Egypt. Kim had for some time wanted to make a film in Iran: she was intrigued by the contrast between the images produced by current-affairs television documentaries and those in the work of Iranian fiction filmmakers. The former portrayed Iran as a country of fanatics, the latter conveyed a much gentler, more poetic sense of the culture and people. As she put it, “you wouldn’t think the documentaries and the fiction were about the same place”. We discussed my 1980s research in Tehran family courts and I gave her a copy of my book, “Marriage on Trial”.

On her personal website, Mir-Hosseini (n.d.) describes herself as ‘a freelance academic, passionately involved in debates on gender equality in law. As a feminist, I expose and criticize the injustices that these laws continue to inflict on women’. We get a clear sense of Longinotto and Mir-Hosseini’s shared sense of purpose in making the film. Mir-Hosseini was able to align her feminist approach with Longinotto’s based on their previous work and their shared motivations for making the documentary. As Smaill (2009) and Larke-Walsh (2019) confirm, Longinotto’s collaborative, compassionate approach is essential to the themes and subjects of her films. She is necessarily biased in favour of her subjects; her camera does not impartially witness events as they unfold. Instead, she co-experiences them with and through her subjects as an active process of ‘wit(h)nessing’, or an ‘encounter with shared earth others (…) seeded in ideas of co-poiesis’ (Boscacci, 2018: 343). Co-poiesis, or co-creation, is central to Longinotto’s work. In outlining her collaborative approach to Divorce Iranian Style and Runaway (also made in Iran), she states that, ‘with Ziba Mir-Hosseini, whom I did Divorce and Runaway with, that really was a collaboration because we became real soul mates. We had very much a shared vision for the film, and I do feel that we collaborated in those two films’ (Longinotto, cited in Smaill, 2007: 179).

Ettinger’s (2001) model also accounts for spectatorial involvement, framing the act of watching as an active process of wit(h)nessing not just for the filmmaker, but also for the audience. Rough Aunties (2008) offers a pertinent example of wit(h)nessing. The film centres on Bobbi Bear, a charity run mostly by women in Durban, South Africa, who support children who have been abused or neglected. Longinotto outlines her collaborative approach, including filming intense scenes of personal trauma. She says that, ‘there are some quite distressing scenes in the film, but we filmed them because one of the group would ring in saying “Kim, you’ve got to come down to the river”, “this is happening” or “you’ve got to come to this house, somebody’s just been shot”. So, it really was a like a family team’ (Longinotto, cited in Thynne and Al-Ali, 2011: 27).

In one such scene, Sdudla, who works for Bobbi Bear, loses her son in a tragic drowning accident, caused by the negligence of a local corporation. Longinotto and her sound recordist are present at the moment shortly after her son’s death where Sdudla is crying as she cradles her son’s dead body. A review of the film outlines how ‘Longinotto films the mother’s agony, and for the first time, I wondered if her camera really needed to record her pain quite so intimately’ (Bradshaw, 2010, n.p.). Longinotto outlines her contradictory feelings on filming this scene:

When we’re by the river and Sdudla’s crying, the sound recordist Mary kept saying to me, “We should stop filming.” And I felt really terrible. I felt like a kind of monster. It’s someone you really love and they’re in pain and you’re filming them. It’s a very strange thing to do. But at the same time I knew that’s what I was there for. And what’s the point of me being there? I don’t want to watch it for the sake of watching it. And I’m there because we’re there as a team and we’re trying to do something about it. And I was so pleased that when they all came to Amsterdam to see the film, when I said, “Do you think I shouldn’t have filmed it?” They all looked at me as if I was mad. Because they’re gonna use that now to campaign, to get companies, not just people digging their drowned children out of rivers, but digging metals out and polluting the rivers and stuff that’s going on all over Africa, where companies are exploiting people and not putting any money back in. Even though it felt a terrible thing emotionally, in my head I knew we had to film it.

The purpose of filming such scenes goes beyond voyeurism. It becomes a form of active wit(h)nessing whereby the act of filming transforms trauma into a tool for purposeful action that includes the audience.

The matrixial also allows us to include the audience in this inter-connected web of wit(h)nessing. Here, the screen itself becomes a ‘veil’, as Ettinger (2001) terms it, or locus of mediation, where the various gazes of creatives and audience meet:

These gazes do not meet in neutral space. As Ettinger (2001: 139) states, ‘if the matrixial gaze conducts traces of “events without witnesses” on to witnesses who were not there, it leads us to discover our part of coresponse-ability [sic] in the events whose source is “inside” oneself: for it prompts us to join in, and be aware of joining in, the traumatic events of others’. The act of viewing therefore includes the audience in the act of wit(h)nessing; however, spectators do so within their particular psycho-socio-economic-political contexts, which shift with each viewing. We can therefore also include these contexts to form the matrixial screen encounter:

Just as viewing takes place within each audience member’s psycho-socio-economic-political context, so does the context of production. The matrixial screen encounter conceptualises this as an interlinked, intersubjective phenomenological encounter rather than a didactic, uni-directional imparting and receiving of knowledge or narrative. This counters ‘conventional documentary history’s overemphasis on the film text and its director as opposed to the institutional structures than sustain and nurture documentary’ (Walker and Waldman, 1999: 4). This model also adds a feminist lens to models of authorship. As White (2015: 10) states:

Feminism is constructed not only in the content or formal codes of women’s cinema, but also through its address to a spectator in whom divisions of race, class and sexuality (and implicitly national identity) as well as gender are subjectively inscribed, and rewritten, through social experience, including that of cinema-going.

Taking Divorce Iranian Style again as an example, the legal context in Iran at this time permitted female children to be married when they reach puberty, which could be as young as 9 years old, often to men who are much older. The film was funded by Channel 4, a commercially self-funded but publicly owned British national television broadcaster. It was commissioned as part of its ‘True Stories’ documentary strand, intended for British and international audiences. This funding context sets up many of the conditions of the film. It must fit the ‘ethos’ and remit of the broadcaster as well as their expectations for that particular strand. As Mir-Hosseini (1999: 17) states, ‘In December (1996), we heard that one of our proposals for funding had come through: Channel 4 TV was prepared to fund us to make a feature-length film for its prestigious True Stories documentary slot. We were enormously encouraged.’ The funding structure under which Divorce Iranian Style was produced sets up the context in which the various ‘gazes’ within the film operate and indicates which may have more power.

The opening scene offers a pertinent example of inter-connected gazes or layers of power. The film was recorded over a period of 4 weeks in November/December 1997 in a family disputes court within the Imam Khomeini Judicial Complex in central Tehran, where the people attending these courts have not reached the decision to divorce by mutual consent. Ziba, a 16-year-old child, is seeking a divorce from her 38-year-old ‘husband’, Bahman, within a courtroom presided over by Judge Deldar, who is male. I place the term ‘husband’ in quotation marks since, although Bahman is legally Ziba’s husband, the marriage took place at the request of their families when Ziba was 14 years old, therefore she had no capacity to fully consent. We hear a female voice-over with what might be interpreted by UK audiences as a middle-class English accent stating, ‘Judge Deldar allowed us to film in his court and made us welcome’. We see Judge Deldar, in his official court robes, take his seat in his courtroom. He looks towards the crew, smiles and offers a warm greeting. This immediately highlights the layers of power that emanate from the socio-economic context of production, whereby a British National broadcaster is commissioning a documentary filmed in the context of a legal court in Tehran in 1998. This layer of power transmits through the gazes of the production crew (Longinotto, Mir-Hosseini and sound recordist Felce), through the gaze of the camera to the subjects and through to the audience. The middle-class English accent of the voice-over strengthens the cultural specificity of the interpreting gaze, already creating a position or mode of interpretation for the audience. The voice-over states ‘the court is informal, we were often drawn into the proceedings. The opening titles read ‘Divorce Iranian Style’. The voice-over continues, ‘A husband has the legal right to divorce but he must get a court order and pay his wife compensation. The court disapproves of divorce and assumes that women want to stay in their marriages’.

Notions of imbalances of power and looking ‘at’ what might be considered the cultural ‘other’ are particularly pertinent here. Since two members of the crew in this scene are white English women, their gaze might be positioned as voyeuristic; however, the matrixial encourages us to acknowledge that when we engage with a filmic text, we are engaging with a web of inter-connected subjectivities. Mir-Hosseini (1999: 17) also acknowledges that her presence and involvement throughout the film, from its inception, counters this presumptive voyeurism:

The fact that the crew had both Iranian and foreign members, I believe, helped transcend the insider/outsider divide. The camera was also a link in this respect, as well as between public and private. We never filmed without people’s consent. Before each new case, I approached the two parties in the corridor, explained who we were and what our film was about, and asked whether they would agree to participate. I explained that we wanted to make a film that foreign audiences could relate to, to try and bridge the gap in understanding, to show how Iranian Muslim women, like women in other parts of the world, do the best they can to make sense of the world around them and to better their lives. Some agreed, others refused. On the whole, and perhaps not surprisingly, most women welcomed the project and wanted to be filmed.

If we focus on the gazes, or layers of power emanating from the crew, mediated by the camera towards their subjects, we can see that their inter-subjective, collaborative, feminist approach to the film supports Ziba’s goal of achieving a divorce, and this support permeates this scene. Ziba glances frequently towards the crew as she makes her case to Judge Deldar. Bahman also attempts to draw their support by frequently glancing at and occasionally directly addressing the crew. After a series of exchanges Ziba assertively asks Bahman, ‘Will you agree to divorce by mutual consent?’ He says immediately, ‘Alight I will’. Bahman looks directly at the crew, nodding towards them; however, we move to a close-up of Ziba, who is looking intently at Judge Deldar. She glances towards Longinotto and Mir-Hosseini, with a faint smile and look of relief. We cut to a mid-shot of Ziba bent slightly over a table as she signs the documents. When she has finished signing, she moves towards Longinotto and Mir-Hosseini, smiling and nodding as she whispers towards them, ‘Divorce by mutual consent! He’s agreed!’ She gives a final nod of relief, directly acknowledging her supporters and demonstrating her confidence that they share her sense of achievement in her securing her divorce from Bahman. As Murray (2018: 94) states:

It is these shifts and movements in (Longinotto’s) camera – the readjustment of point of view or the movement off-centre – there is a demonstration of the separation of camera from the operator. We are no longer watching directly through a “neutral” gaze; instead we simultaneously watch Longinotto’s reaction (…) and we respond to her emotion as well as her subject’s.

The matrixial screen encounter does not eradicate the notion that there is an imbalance of power between filmmaker and subject, nor does it equalize the varying degrees of power in the production context. In this scene, the feminist gaze adds an additional layer of power that Ziba utilises to her advantage in achieving her aims; however, if the socio-political context of production is deeply patriarchal, as we see in this family court in Tehran, there is no guarantee that the addition of a supportive female gaze behind camera will significantly shift this imbalance of power. Divorce Iranian Style therefore also ‘reveals how difficult it is for women to make their rights effective under Sharia Law’ (Merás, 2018: 174). The power of the patriarchal system is exemplified when Ziba asks, ‘By the way, what’s the legal age a girl can be married?’ We hear Judge Deldar answer, ‘When she reaches puberty’. Ziba says, ‘There must be legal age’. The camera pans briefly back to Judge Deldar, who looks towards Ziba and quietly states, ‘A girl can reach puberty at 9 and then she can be married.’ The gaze of Longinotto’s camera remains focused on Ziba as she looks uncertain and dissatisfied as she anxiously presses her lips together. As Murray (2018: 94) states ‘the readjustment of point of view or the movement off-centre – allows for revelations of “affective dissonance” within her subjects and, at these moments, their voices direct the action of the camera’. Ziba walks towards the desk at the back of the room where two women, who work in an administrative capacity for the court, are seated. An Iranian flag, signifying the power of the state, is in the foreground of the shot. One of the women passes Ziba a file with papers inside. We cut to an external shot of the court, where a large image of the Ayatollah Khomeini (Supreme Leader of Iran from 1979–1989) hangs on the building in a prominent position. Whilst this imagery might seem to promote Iran as the cultural ‘other’, it also highlights Ziba’s position, not as a passive recipient of state power, but as an active agent who is actively asserting her rights within that system, therefore ‘defy(ing) the perceived notions of Muslim women as subjects without agency’ (Merás, 2018: 174). As Mir-Hosseini (1999: 17) states:

We had to distinguish what we (and we hoped our target audiences) saw as ‘positive’ from what many people we talked to saw as ‘negative’, with the potential of turning into yet another sensationalized foreign film on Iran. Images and words, we said, can evoke different feelings in different cultures. For instance, a mother talking of the loss of her children in war as martyrdom for Islam, is more likely in Western eyes to confirm stereotypes of religious zealotry and fanaticism, rather than evoke the Shi’a idea of sacrifice for justice and freedom. What they saw as positive could be seen as negative in Western eyes, and vice versa. One answer was to present viewers with complex social reality and allow them to make up their own minds. Some might react favourably, and some might not, but in the end, it could give a much more ‘positive’ image of Iran than the usual films, if we could show ordinary women, at home and in court, holding their own ground, maintaining the family from within. This would challenge some hostile Western stereotypes.

This opening scene exemplifies what Longinotto (interview with BFI, 2013) refers to as a ‘play within a play’. Bahman and Ziba are clearly aware of the camera and the crew, and both attempt to draw the camera and the audience in to support their positions. Ziba’s frequent glances towards the supportive gaze of the crew strengthens her position in the courtroom. Their partiality is clear: the camera is not a neutral witness but is necessarily partial to Ziba’s aims. This inter-subjective feminist solidarity strengthens Ziba’s power and sense of agency. As Mir-Hosseini (1999: 17) states, ‘The presence of an all-woman crew changed the gender balance in the courtroom and undoubtedly gave several women courage’.

Conclusion

The matrixial screen encounter resonates with the postmodern, post-structuralist turn in film theory and phenomenology. As Doyle (2001: xiii) states, ‘much of what we think of as critical of postmodern thought is, (…) postmodern phenomenology’ and that much of this thought ‘aspires to (…) immersion in the unfixed, fluctuating and necessarily temporal play of signs and surfaces’ (ibid.: xvi) that ‘share an interest in the local, the lived, the decentred and the untotalizable’ (ibid: xiii). Longinotto’s collaborative approach, with her emphasis on the localised, lived experience of women could be viewed as a form of postmodern phenomenological filmmaking. The matrixial screen encounter provides a model that theorises this collaborative, inter-subjective approach. By substituting the womb for the phallus and by disputing any clear distinctions between I and Other, Ettinger rethinks the creative process in a way that rejects Griersonian, direct cinema and auteur-influenced models of documentary in favour of a model that acknowledges the complexity of highly collaborative practitioners like Longinotto.

Ettinger’s reconceptualization echoes Barthes (1977) classic notion of the ‘death of the author,’ but eschews such extremes of creative erasure, framing instead a wider process of ‘encounter’ between context, text and consumption that invokes authorship without relying on it as the sole or even the primary source of meaning. Pearlman and Sutton (2022: 86) in their work on distributed authorship outline the necessity of re-thinking the persistent culture, particularly in film, that tends to over-emphasise the director-auteur-model model of authorship:

Filmmaking is one of the most complexly layered forms of artistic production. It is a deeply interactive process, socially, culturally, and technologically. Yet the bulk of popular and academic discussion of filmmaking continues to attribute creative authorship of films to directors. Texts refer to ‘a Scorsese film’, not a film by ‘Scorsese et al.’. We argue that this kind of attribution of sole creative responsibility to film directors is a misapprehension of most filmmaking processes, based in part on dubious individualist assumptions about creative minds.

The individualistic director-as-auteur model undermines the complexity of the layers of gazes and power within any filmic text but is particularly pernicious when applied to documentary film. Resisting this longstanding habit of thought, the matrixial screen encounter maps the inter-connected, inter-subjective gazes, or layers of power which take place within the psycho-socio-economic-political contexts of production and consumption. Including the production context not as a singular author, but as a collective effort allows us to consider how this layer of power filters through the gazes of the crew, the camera, the subjects and ultimately to the audience. This model is not limited to Longinotto, to documentaries that have an expressly feminist subject matter or ethos, or to documentary in general. It can be applied to any filmic text that involves multiple creatives and/or actors/subjects, challenging the prevailing trend that ‘nonexplicitly feminist work remain(s) unaffected by feminist thinking (Walker and Waldman, 1999: 5).

Overall, the matrixial screen encounter offers a theoretical framework tool for teaching women’s filmmaking that ‘presents a challenge to traditional conceptions of the author/auteur, embedded in Euro-Western exceptionalist individualism’ (Ulfsdotter and Backman Rogers, 2018a: 5). As Walker and Waldman (1999: 2) state, ‘happily, documentary studies is a place where such connective theorizing can flourish’. The matrixial screen encounter offers an alternative to the phallocentrism of the unitary, authoritative gaze of the auteur and the impartiality of the camera-as-observer, situating the screen as a locus of mediation where all these various matrixes meet.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Barthes, R 1977 The Death of the Author. London, UK: Fontana.

BFI 2013 Ask a Documentary Filmmaker: Kim Longinotto. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KYcekCtOKDk [Accessed 01/11/2021]

Boscacci, L 2018 Wit(h)nessing. Environmental Humanities, 10 (1): 343–347. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-4385617

Bradshaw, P 2010 Rough Aunties. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/jul/15/rough-aunties-film-review [Accessed 21/12/2021]

Bruzzi, S 2006 New Documentary: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203967386

Butler, J 2005 Giving an Account of Oneself. New York, NY, USA: Fordham University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5422/fso/9780823225033.001.0001

Cochrane, K 2010 Kim Longinotto: “Filmmaking saved my life”. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/feb/12/longinotto-film-making-saved-life [Accessed 01/11/2021]

Coorlawala, U 1996 Darshan and Abhinaya: An Alternative to the Male Gaze. Dance Research Journal, 28(1): 19–27. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/1478103

Cousins M and Macdonald K 2006 Imagining Reality. The Faber Book of Documentary. London, UK: Faber and Faber.

Doyle, L 2001 Introduction. In: Doyle, L (ed.) Bodies of Resistance. New Phenomenologies of Politics, Agency and Culture. Evanston, IL, USA: Northwestern University Press. pp. xi-xxxiv.

Ettinger, B L 2001 Matrixial Gaze and Screen. Other Than Phallic and Beyond the Late Lacan. In: Doyle, L (ed.) Bodies of Resistance. New Phenomenologies of Politics, Agency and Culture. Evanston, Illinois, USA: Northwestern University Press. pp. 103–143.

French L 2018 Women in the Director’s Chair: the “Female Gaze” in Documentary Film. In: Ulfsdotter, B and Backman Rogers A. (eds.) Female Authorship and the Documentary Image: Theory, Practice and Aesthetics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 9–21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9781474419444.003.0002

Larke-Walsh, GS 2019 Compassion in Kim Longinotto’s Documentary Practice. Feminist Media Studies, 19 (1): 147–160. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1399430

Malone A 2018 The Female Gaze. Essential Movies Made by Women. Coral Gables, FL, USA: Mango Publishing Group.

Merás L 2018 Profession: Documentarist: Underground Documentary Making in Iran. In: Ulfsdotter, B and Backman Rogers, A (eds.) Female Agency and Documentary Strategies. Subjectivities, Identity and Activism. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 170–183. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781474419482-016

Mir-Hosseini, Z 1999 The Making of Divorce Iranian Style. ISIM Newsletter, International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World, 2 (1): 17. https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2729373/view [Accessed 02/11/2021]

Mir-Hosseini, Z (n.d.) Ziba Mir-Hosseini. Legal Anthropologist and Activist. http://www.zibamirhosseini.com/ [Accessed 02/11/2021]

Murray, R 2018 Speaking About or Speaking Nearby? Documentary Practice and Female Authorship in the Film of Kim Longinotto. In: Ulfsdotter, B and Backman Rogers, A (eds.) Female Authorship and the Documentary Image: Theory, Practice and Aesthetics. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 90–106. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781474419451-010

Nichols, B 2001 Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Pearlman, K and Sutton, J (2022) Reframing the director: distributed creativity in filmmaking practice. In: Hjort, M and Nanicelli, T (eds.) A Companion to Motion Pictures and Public Value. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 86–106. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9781119677154.ch4

Renov, M 2012 Theorizing Documentary. London: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203873083

Smaill, S 2007 Interview with Kim Longinotto. Studies in Documentary Film, 1 (2): 177–187.

Smaill, B 2009 The Documentaries of Kim Longinotto: Women, Change, and Painful Modernity. Camera Obscura: A Journal of Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies, 24 (71 2): 43–75.

Smaill, B 2015 The Documentary. Politics, Emotion, Culture. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Snow, E 1989 Theorizing the Male Gaze: Some Problems. Representations, 25: 30–41. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2928465

Thynne, L, Al-Ali, N and Longinotto K 2011 An interview with Kim Longinotto. Feminist Review, No. 99: 25–38. http://www.jstor.com/stable/41288873. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2011.47

Ulfsdotter, B and Backman Rogers, A 2018a Introduction. In: Ulfsdotter, B and Backman Rogers, A (eds.) Female Authorship and the Documentary Image: Theory, Practice and Aesthetics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–6. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781474419451-004

Ulfsdotter, B and Backman Rogers, A 2018b Introduction. In: Ulfsdotter, B and Backman Rogers, A (eds.) Female Agency and Documentary Strategies. Subjectivities, Identity and Activism. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–6. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781474419482-004

Walker, J and Waldman, D 1999 Introduction. In: Walker, J and Waldman, D (eds.) Feminism and Documentary. Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 1–35.

White P 2015 Women’s Cinema, World Cinema. Projecting Contemporary Feminisms. Durham, NC, USA: Duke University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1215/9780822376019

Filmography

Divorce Iranian Style, 1998. [Documentary] Directors: Kim Longinotto and Ziba Mir-Hosseini. Channel 4: Iran/UK.

Gaea Girls, 2000. [Documentary] Directors: Kim Longinotto and Jano Williams: Japan/UK.

Pride of Place, 1976. [Documentary] Directors: Kim Longinotto (as Kimona Landseer) and Claire Pollak: UK.

Rough Aunties, 2008 [Documentary] Director: Kim Longinotto: South Africa/UK.

Shinjuku Boys, 1995. [Documentary] Director: Kim Longinotto and Jano Williams: Japan/UK.

The Day I Will Never Forget, 2002) [Documentary] Director: Kim Longinotto: Kenya/UK.